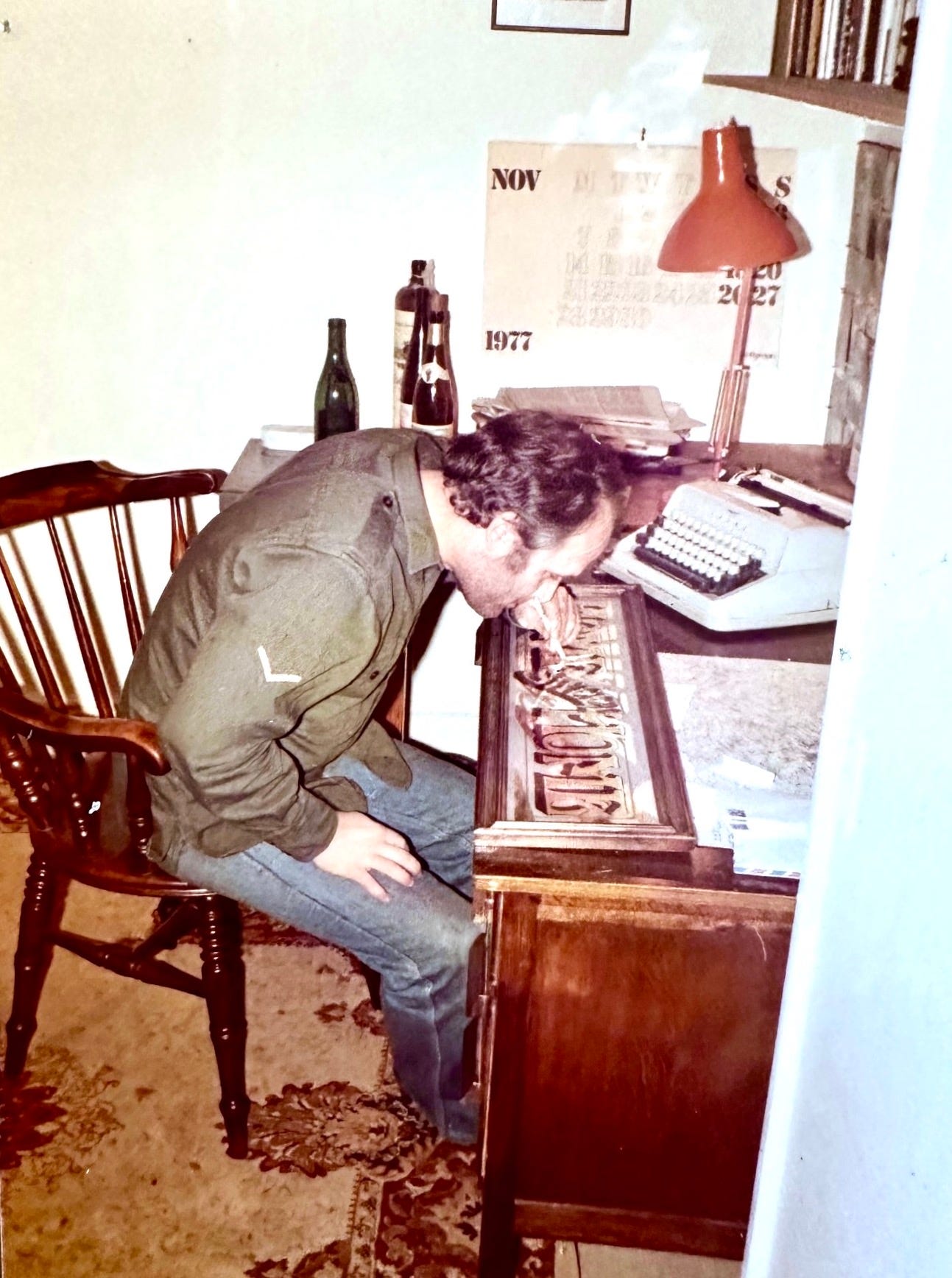

I conducted this interview (unpublished until now) in mid-1979.

Tim died from an overdose of heroin in Hollywood on 29 December 1980.

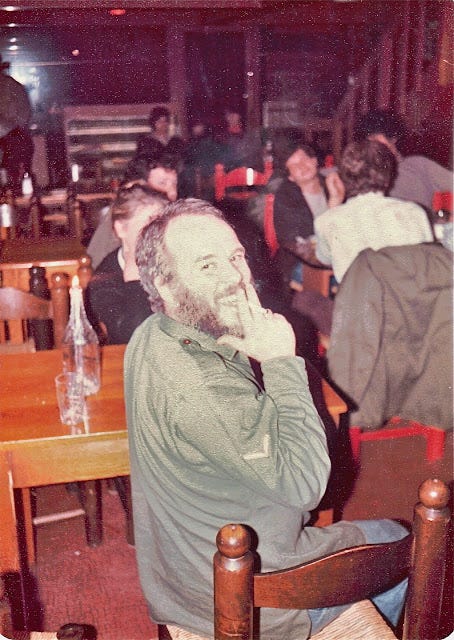

Tim Hardin used to live in a squat (a derelict house) around the corner from Tricky Dick's, my mid-1970s late-night coffee house in Hampstead, north London.

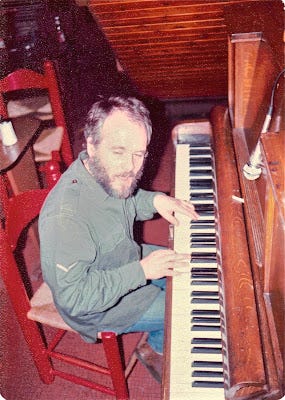

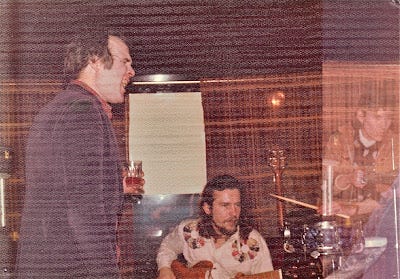

One evening, Tim wandered in and played his guitar—a very powerful performance featuring his mighty voice and self-written classics like "If I Were a Carpenter" and “Reason to Believe.”

We became friends and, somewhat down and out, he'd hang with me through the day as I made supply runs for coffee, ice cream, etc.

Early evening, we'd hang at the local bars: Swiss Cottage, The Red House and The Old Bull and Bush, where he'd alternately make fast friends and provoke fights.

Later, Tim would play a set at Tricky Dick's in exchange for a burger and fries (and a pint of whiskey under the table).

Many customers had no idea he'd been a famous pop star, having fallen on hard times, and when he improvised new lyrics extemporaneously they'd prat-call him, hollering that the words were wrong.

Once, Tim stopped playing and smacked a smug heckler on the stomach. But mostly he played, because that's what he liked doing best of all. He lived for his art and felt good only when he was in his zone, strumming, tapping keys and singing.

ERINGER: Tell me about your rise and fall situation?

HARDIN: When I was 19, I got a scholarship at the American Academy of Dramatic Art in New York. It was too much like school, so after about six weeks I dropped out and bought a guitar with my last 40 bucks. Didn't know how to play it or anything. Figured out five or six chords and started writing tunes because it was easier than learning other people's songs. I got a gig in Greenwich Village where they passed the hat, hot dog money and bus fare. Out of that I got a publishing deal: I'd send them a song, they'd send me some bread.

The music business is based, like every other business, on making as much money as you can for as little effort and as little time spent as possible. There are some people who do not know how to coordinate their lives that way. They find out something they can do that's exciting for them to do, which in my case is singing and playing. It's the only thing I can do good enough to make me feel good. So, helplessly I go, feeling good and playing, not knowing that when somebody says, "I want to make you a really fair contract"—not knowing that they don't feel the same way about their gig as I do about mine. It's a business where if you can't lie, or if you don't have somebody to tell you that somebody else is lying to you, you're always going to lose. Just always. You might stack up some bread, but you're going to feel such a fool when you realize you're only getting one percent of what you're supposed to get.

You know, I said to my first contract people, who screwed me real good, "I said, ‘Should I have a lawyer look at this contract?’ They said, ‘Sure, our lawyer's right next door!’” Hey, man, almost everybody knows better than what I did.

When I realized what was going on, I just walked on them, split, which also cost me a lot of money. At that time I was so young and, it seemed me, so rich, that I couldn't make a mistake. That I had some money in my pocket made me so fucking cocky I decided to stop recording for anyone and start my own record company.

ERINGER: When was that?

HARDIN: About 1972. But then I got an offer to record with Rod Stewart's people, GM Records.

ERINGER: That's when you moved to London?

HARDIN: Yeah.

ERINGER: Why London?

HARDIN: Well, romantically I had something going with Mary Frampton.

ERINGER: While she was married to Peter Frampton?

HARDIN: Yeah.

ERINGER: Did Peter know?

HARDIN: No, he didn't. And neither did she! I was just so in love with her that I just went over to London and waited till somebody fucked up.

ERINGER: What happened?

HARDIN: Well, I didn't fuck up, so I got it.

ERINGER: Got what?

HARDIN: Mary married me.

ERINGER: How were you for money at that time?"

HARDIN: Until just after Christmas, '75, I never realized that I wouldn't have all the money I ever wanted ever.

ERINGER: After being a millionaire for a bunch of years you were suddenly broke?

HARDIN: And would be in terms of anything I could make off of what I thought I owned. Then my manager, a so-called "friend," came over and said somebody offered me a quarter-of-a-million for my catalog of songs. Well, I needed money at the time so I said okay. When I came round to my senses a week later, I changed my mind. So this "friend" came to England and told me he'd gone to the IRS and told him my story about the kind of tax shortcuts everybody takes, and he said they'd extradite me from England and put me in jail. So I signed the paper and sold the catalog.

ERINGER: But, still, how can you be so down and out?

HARDIN: I had to pay my ex-wife Susan an awful lot of money. I wish she'd give me some.

ERINGER: Why won't she?

HARDIN: Because she knows I hate her so much and she hates me, too. She doesn't even like to see me.

ERINGER: When did you last see her?

HARDIN: About seven months ago. She met me at her office, where she does organic make-up. I had tea and a cupcake with her. I asked her if she could lend me some bread to pay for parking across the street. She said, "Oh, Tim, are you really broke?" and I explained the whole thing to her. So she gave me 20 bucks instead of five. She could tell right then that I was very capable of killing.

ERINGER: So, back in London with no money. What did you do?

HARDIN: I got broke so fast. I didn’t have a place to stay anymore. I couldn’t pay my hotel bill. Everything got real bad, real quick.

ERINGER: How did it feel when it finally occurred to you that you were dead broke and had to change your glamorous lifestyle?

HARDIN: It grabbed me by the nuts, put its thumb up my asshole and scratched my brains from inside.

ERINGER: You were addicted to heroin, right?

HARDIN: My drug experiences were not a drag. I felt so good so much that I will never, ever be sorry. I was addicted to heroin from age 19 to 26—and then I went on to methadone, which is even better!

ERINGER: Didn't you once tell me you shot up with Keith Richard?

HARDIN: Once? Ha! Once every three or four hours for a couple of weeks.

Amazing find for me to come across. Love TH 🫂🫶 thank you