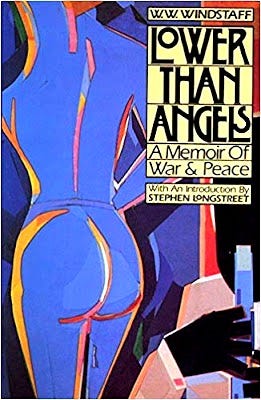

I discovered this lost document and co-published it as an Enigma Book with Bartleby Press in 1993

By late 1917 we tired rummies and crocks were aware of how crazy and sick the war was. After all the flying, the Vickers gun bursts; no flags waving, no gallant charges, no Red Cross nookie; maybe a hairy kiss on the cheeks by a French general.

As we flew we knew below us five, six million filthy men were buried alive underground, living like crazy, red-eyed rats in their own shit and piss, decaying comrades' entrails. Years of burrowing, rotting away, dying with silly shocked gestures to gain, retain, fifty yards, a hundred yards. Then back into the crap and cootie hells, the stink of unburied dead from 1914 on, all those rotting horses too. In the air we missed a war that smelled of manure, putrefying generations of dead schoolboys and fathers. We fliers could only smell it sometimes as we came in at dusk, back from patrol, flying low over the trenches that stretched in the earth from the English Channel to the Swiss. When you went to mess with the line officers, they smelled of it, their eyes bulging with madness, maybe fear...

When he wrote this memoir over sixty years ago, the author planned a privately printed edition as gifts for his friends. He chose a pseudonym, W. W. Windstaff, to avoid embarrassing his socially prominent family.

He did not view himself as a writer, and wrote his story with an intensity and honesty innocent of literary pretension.

Windstaff led a colorful life. Entranced by airplanes, he joined the British air force as a pilot during World War I. Following his convalescence from a combat wound, Windstaff went to Paris and witnessed the grand American invasion during the 1920s. His descriptions of Harry’s Bar, of the cafes of Hemingway and Joyce, are the clearest and truest of that era. He drank with the artists, but preferred the company of gamblers, ex-soldiers, and race-track people.

Mid-decade, Windstaff returned to America and settled for a time among the flappers and speakeasies of Greenwich Village. He then went back to Europe and found Paris had changed. Well fed, but unhappy as the kept man of a pampered, older woman, Windstaff escaped to Rome to find a childhood friend.

By the end of the ’20s, Windstaff was back in the States, trying to overcome alcoholism, hoping to find stability. With the assistance of Stephen Longstreet, then a budding writer and painter, he began writing this memoir.

In a unique style, Lower than Angels captures the essence of war with wonderfully descriptive passages of air combat, and of life on the ground. Later, Windstaff vividly memorializes the expatriate experience.

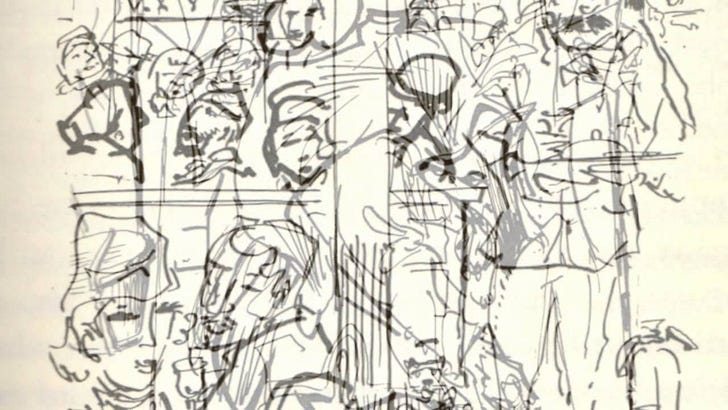

Stephen Longstreet, editor and illustrator of Lower than Angels, was perhaps only slightly less enigmatic than author W.W. Windstaff. To learn more about Longstreet and his unique life as author and artist, visit the official Stephen Longstreet website.

More than simply a memoir of fascinating times, Lower than Angels is a raw and powerful portrayal of a man who could not overcome the trauma of war, and survived with a veneer of cynicism aided by the bottle.

“…reads like an unholy but effective collaboration between Hemingway and Howard Stern.”

David Streitfield, Washington Post

“We know all about Gertrude and Alice, Ernest and Scott, Ezra and so on, some living high and some low as the ‘20s roared away from the hecatomb of the World War. There were thousands of Americans in Paris in those years, not all of them famous, of course, and not all of them sloshed at the Ritz. So meet W. W. Windstaff, often sloshed but not at all famous, and so modest that 60 years after his death he wishes to remain anonymous.”

Katherine Knorr, International Herald Tribune

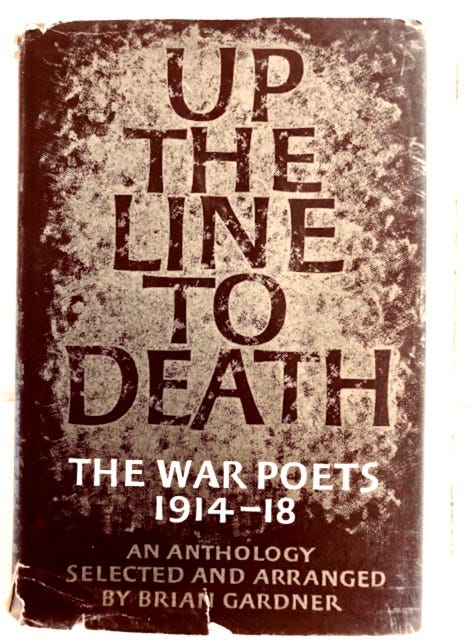

I purchased this book in 1969 from High Hill Bookshop in Hampstead Village, London.

Don't know what attracted me to it at age 15, but it has followed me everywhere.