GONE BERSERK: 3) ARRIVAL IN ICELAND: THE KLEPPUR

From 22 Years Ago: Reflection, Rumination & Rhetoric From the Road

January 2002

Alpha 26 is waiting outside the Lowndes next morning. We toss our bags into the back of his mobile pasture and join Erik the Red inside. Erik is excited because he thinks he’s returning to his Viking roots, or maybe a past life, he’s not certain which but eager to find out. What immediately commences is The Erik Show, a montage of fantastical stories about himself: Forrest Gump meets Big Fish—or Erik’s own version of berserk.

En route to Heathrow Airport at high speed, Erik’s ideas of reference are already out of control, Van Stein expounds on why-notism and Alpha 26 cautions about the dangers of looking for the devil in Iceland. “It already knows who you are,” he says, “where you are, and what you’re thinking.”

And I’m thinking, who needs Iceland for berserk?

Floater is waiting for us in the departure lounge having just jumped the pond, a bit groggy but otherwise eager for whatever madness may come next, still surprised this trip is actually taking place.

When boarding is called for our Iceland Air flight to Reykjavik (which Van Stein keeps calling Wreck-it-up) we find a motley group of fellow passengers at the gate.

Thorrablot celebrants?

The pilot speaks in his native tongue and says things that sound like, “Thorazine is available” and “Lech Walesa will meet you at the gate.” Then he hands the microphone to the chief flight attendant and she says, “Head sex will be given.”

She provides ice for a round of Fernet-Branca, which I carry in miniatures, not because this herbal digestif is a remedy for eating sheep testicles, but because Van Stein and I actually enjoy its medicinal bitterness.

Our collective anticipation runs high during the final approach over glacier and lava field. Surprisingly, it is not completely dark at 4:30 in the afternoon when we skid to a halt and disembark.

But it is cold.

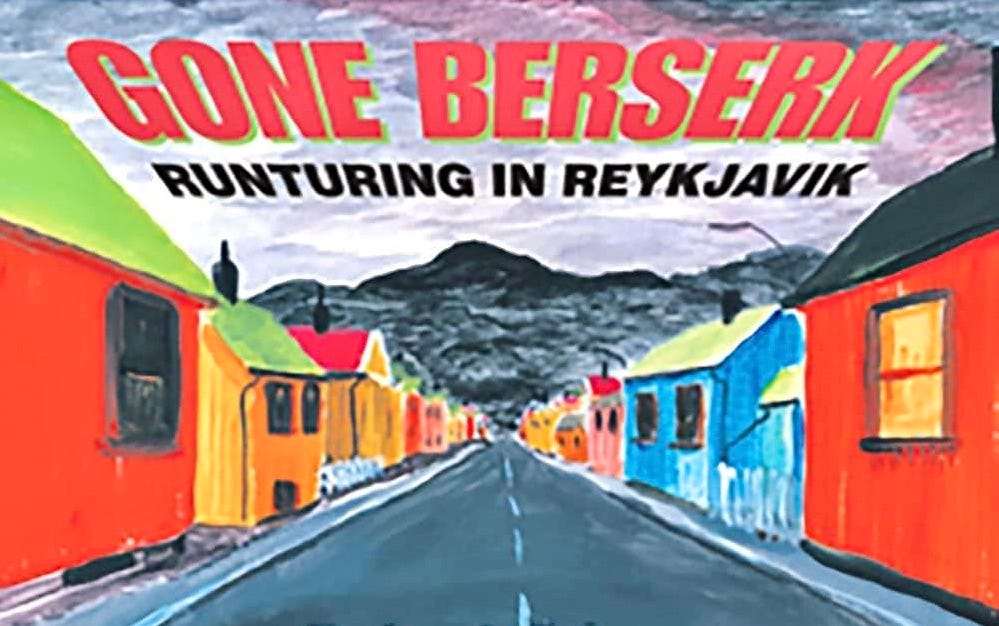

Kristjan Kristjansson, our guide from Mountain Taxi, guides us to his four-wheel Patrol.

Seated in front, I study lunar topography, a setting sun, and full moon…

…a moon, says Kristjan, that is always out during the winter.

Talk about a nocturnal artist’s dream: A moon that never sets.

A Disturbing Calm

Even more striking is the quiet.

A disturbing calm.

Van Stein bounces around the back seat, twisting and turning, eyeing the skyline: big sky, low line. Even Reykjavik, in the distance, is lying low.

We pass an aluminum smelting plant. Its presence embarrasses our driver, and he apologizes for it.

“No,” says Van Stein. “I could make a very beautiful painting out of that.”

This is the precise moment Kristjan realizes we are not his typical sightseers.

The city outskirts include strip malls with omentum parlors like McDonald’s and KFC and Subway—and much colorful graffiti. (“Graffiti is universal,” comments Van Stein.)

Hotel Holt is in 101, Reykjavik’s most fashionable neighborhood.

We check in, dump our bags and quickly re-group for a tour of glacial chic.

Kristjan cruises Laugavegur, the Capital of Cool’s main drag, crawling distance from our hotel. Bars and cafes abound. Runtur territory. Not quite what I expect: the calm, the quiet, the quaint corrugated metal houses painted in deep reds and fantasy blues and bright yellows with interiors that glow orange.

But it is only Thursday. Weekend berserk-ness is a whole day away.

Kristjan drives onto a wooden pier at the port and we climb out. An Arctic wind blows in from a place called Glacier, visible a hundred miles away in the moonlit sky, such is the clarity in this oxygen-pure environment.

Onto The Dome, a contemporary building at Reykjavik’s highest point with a revolving restaurant called Pearl. Van Stein risks frostbite to erect a tripod on the balcony to snap photos for his imagery archive.

Catching the Klepp

Back in the Patrol, I pose a question for Kristjan Kristjansson: “Do you have a mental hospital in Reykjavik?”

He studies me with a long sideways look, not sure he heard right—and if he did, he is quietly alarmed.

“You know,” I add. “A madhouse. Where they keep crazy people?”

“Ah.” Kristjan pauses. He heard right. “Yes.” He hopes this will conclude the subject.

“Does it have a name?”

Kristjan considers this, hesitates. It is clear he would rather talk about something else. Anything else. “Uh, people here call it House by the Blue Bay. When anybody acts crazy, we say, be careful or you will go to the House by the Blue Bay.”

Van Stein erupts like a volcano. “Why is it called that?”

“It’s by the bay,” replies Kristjan. “The blue bay.”

“Far from here?” I ask.

“About 15 minutes.”

“Can we see it?” I ask.

If Kristjan prides himself on anything, it is his skill as a guide. But my request crosses an invisible boundary, and he is stumped. Another sideways look, a shrug, then resignation. “If you want, I take you.”

In all his tours, and he has given many, no one has ever asked Kristjan about the local loony bin. Not only do we ask, we want to see it.

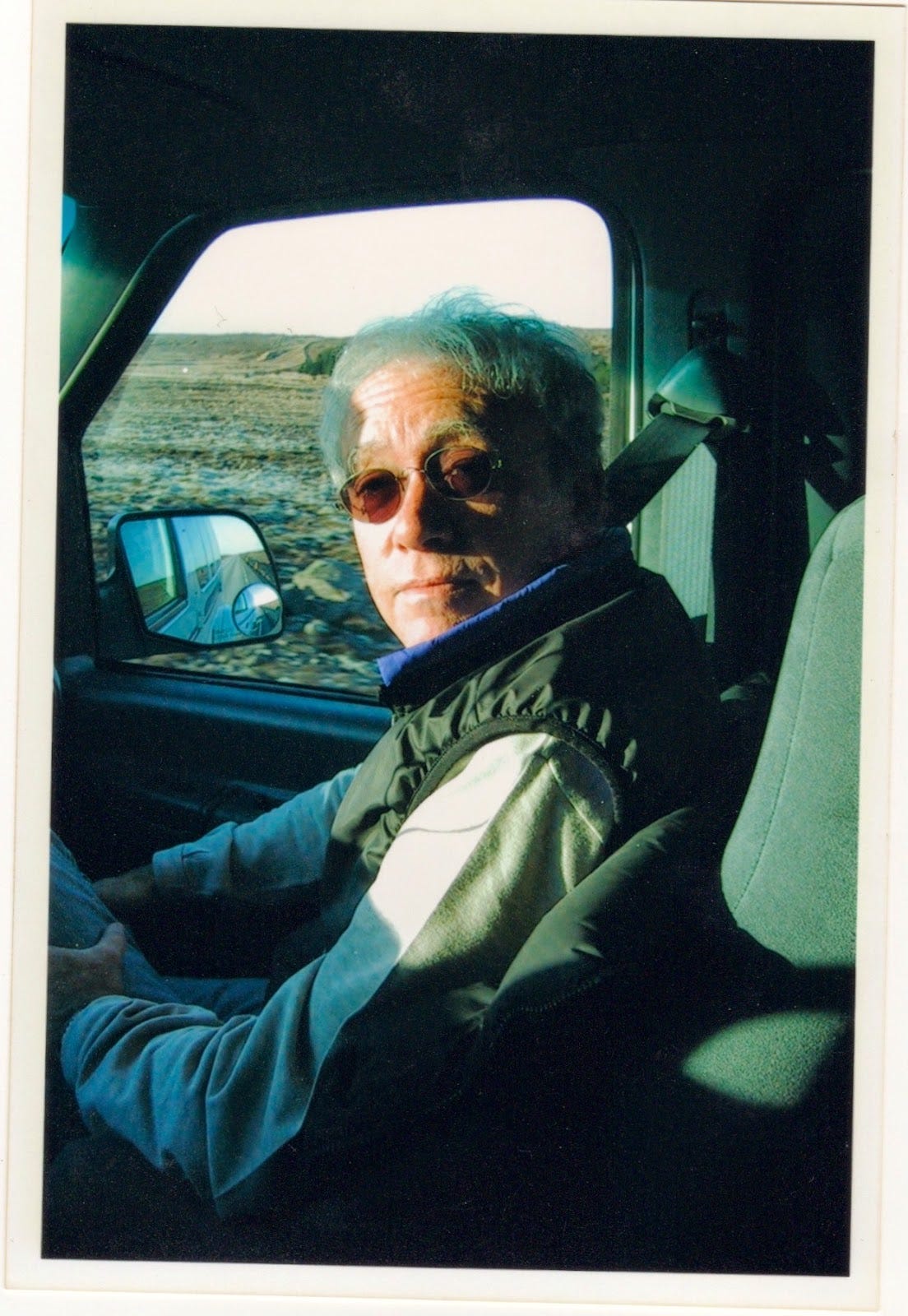

About 15 minutes later we roll into a desolate neighborhood. Trees and hedges—the first we’ve seen in this generally tree-less city—conceal a building. Beyond, the so-called blue bay shimmers beneath moonlight. Kristjan gestures at a street-sign: Kleppskaft. An arrow points left. “This is it,” he says solemnly. “The Kleppur.” He hopes this is enough to satiate our curiosity.

“Can’t we get nearer?” asks Van Stein.

A shiver seems to runs up Kristjan’s spine. Then he eases onto Kleppskaft. The building comes into view: An L-shaped structure, three floors with sloped roof and dormer windows illuminated by soft orange light. I turn to Van Stein. “I think you’ve got to catch the Klepp.”

My comment is redundant; Van Stein is already mesmerized by the imagery—and its significance to going berserk. “Can we get out, look around?” he asks.

Iceland’s Insanity Stigma

This discomforts Kristjan more than ever. He circles, finds a safe place for his vehicle near some bushes and signals us to alight. If we must.

We must and we do. Van Stein scouts angles while Erik the Red shoots photos.

Floater chooses warmth and remains inside the vehicle. Kristjan does not budge from behind the wheel, which he grips tightly with both hands.

The temperature is ten-below, an icy wind blowing in from the blue bay. Erik and I re-join Floater, but Van Stein, insulated in long johns from Patagonia, mulls around, committing himself to the Klepp.

“Let’s go,” I say. “That crazy artist belongs here.” It does not take much convincing. Kristjan releases the handbrake, eases off.

“Hey!” hollers Van Stein. He runs, catches up, jumps into the slow-moving vehicle. “What’s that?” He points at a free-standing building within the compound.

“The Rock Shop,” replies Kristjan.

For a guy who hates to visit this place, he seems to know an awful lot.

“They sell rocks here?”

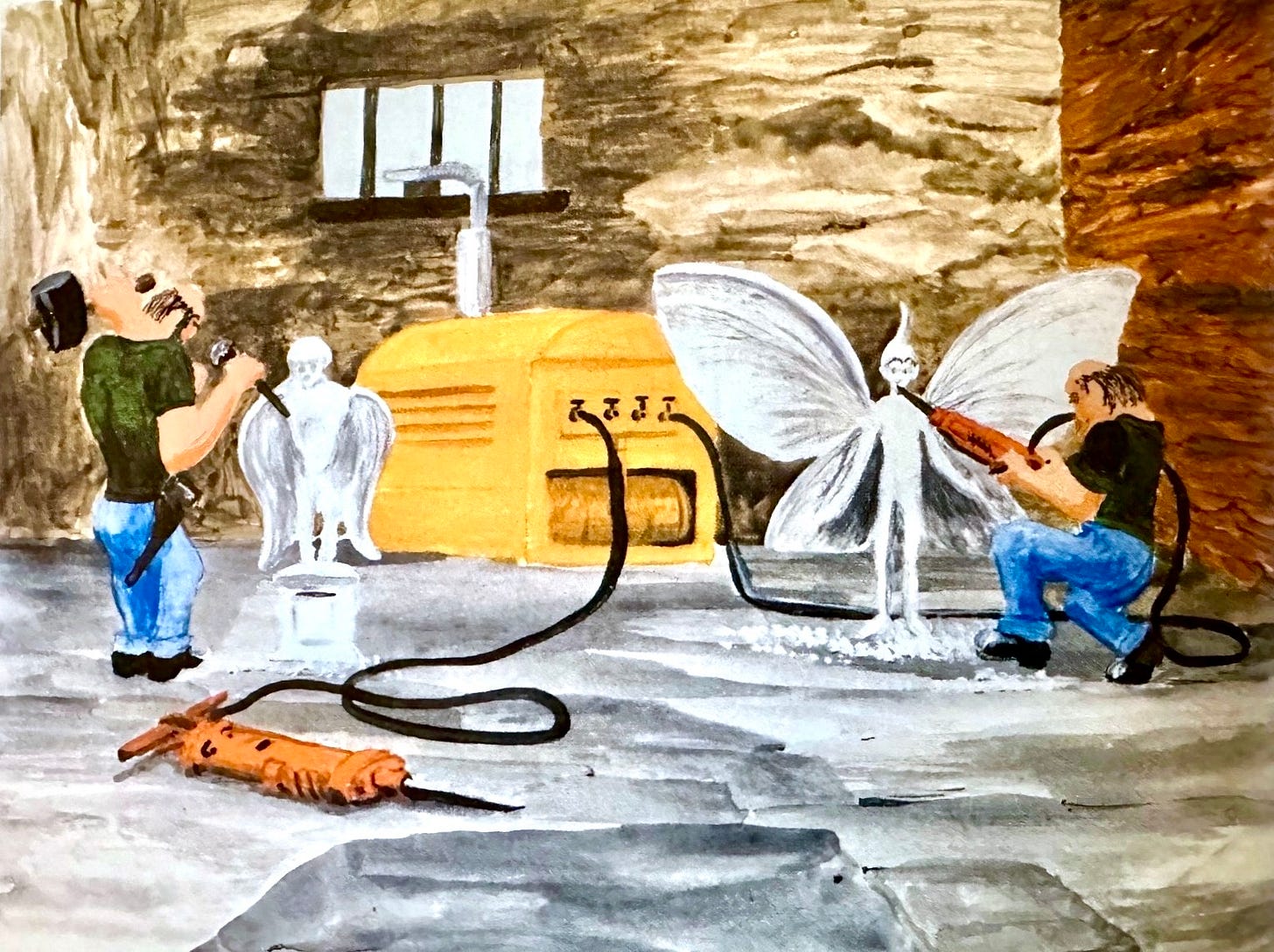

“Sculpture.” Kristjan shudders. “Therapy for the patients.” Kristjan is visibly relieved to roll out of Kleppskaft. “Most people are frightened to come here,” he says, finally revealing his thoughts.

“Frightened of what?” I say. “Insanity?”

Kristjan nods. “Once people come here, they never fit back into society.”

“You mean they get stigmatized?” I say. “Icelandic society holds them forever at sword’s length?”

Kristjan nods.

Our first night in town and we have uncovered a serious irony about berserk-ness: Iceland’s population, descended from fearless Viking Berserkers, is petrified of… insanity.

Which is linked, no doubt, to one better-known fact: Iceland’s suicide rate is the world’s highest.

Lunacy, for these Nordic folk, lurks just around the corner, just one wrong turn away. Not only do they know this, they are so petrified of insanity they hold it against each other.

And we haven’t even seen their art yet.