IN MEMORY OF NAN (BORN 10 DECEMBER 1901)

Sunday, Spiritual

Like many others of her generation, my maternal grandmother’s life was shaped by two world wars. She met her husband, an Englishman, during The War to End All Wars—and lost her only son to the war after that.

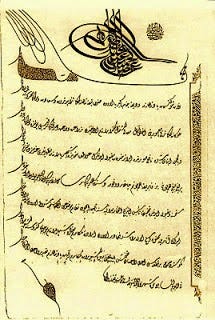

Nan was Armenian, born in Istanbul—or “Constance,” as she called it. Her family was spared from the Turkish genocide because her father, Azarik Kalfayan, was a master craftsman of fine rugs, known as “Kalfayans.” The Turks viewed Armenians as extinct-able. But, alas, good rug-makers were not, so the Emperor provided Azarik with a “Get-out-of-genocide-alive card,” more formally known as a Certificate of Personal Satisfaction.

Nan’s parents did not care for the notion of an English occupier as a son-in-law. Edward Stanley and his fellow British soldiers frequented the necktie shop where my grandmother, Adrine, worked, all of them vying to win her heart by purchasing more neckties than they needed.

My grandfather won. When her parents forbade the match, Nan threatened to join a convent and become a nun if not permitted to marry the man she loved. Her parents relented.

But this did not prevent a similar situation in England, where the couple soon settled. Pop’s family treated Nan like a second-class relative, a half-notch above a wog.

My uncle was born, followed by my mom.

I would never meet my Uncle Edward. His passion was flying, and when World War II began he joined the Royal Air Force, captained a bomber and perished over Burma. My uncle could have bailed out along with other crew members who lived to tell their POW stories. However, an injured crewman could not bail so my uncle chose to remain at the controls of his wounded plane, hoping to land it.

The depths of emotional trauma that result from losing a son surely transcend language. Perhaps it was at this juncture that Nan first tottered near the edge.

My uncle was considered MIA; his body never found. But Nan refused to give up hope that he was alive somewhere. A boardwalk clairvoyant once told her he was living on a tropical island. Uncle Edward’s other passion was stamp-collecting and she kept his album safely tucked away for his return. But he never returned and now it belongs to me. (Some suggest I get this collection appraised but I refuse to demean it to a numeric value.)

My mother met my father through World War II. (But for WWI and WWII, and all its misery, I would not be here.) My dad was a GI stationed in London.

He met my mom at a dancehall in Potters Bar, a suburb where my mother grew up. Their romance survived several separations, first, when my dad shipped to Paris, and then at war’s end when he shipped back to the Bronx. He returned to England to marry my mom—and shipped her back with him to New York City.

My older brother was born two years later. Then Nan and Pops moved to New York to be near their daughter and her family.

My father wanted to be an actor. He was a cast member of Mister Roberts on Broadway, performing alongside Henry Fonda. But it wasn’t happening fast enough for him and he had a wife and child to support. Plus he was plagued by tinnitus. So he put his family and all their belongings into a car and drove cross-country to California, believing a change of scenery might help. That’s where they had me. Nan and Pops stayed behind in New York, and visited at least once.

When I was about four, Pops got sick and, because I was a cuddly, clingy toddler, my mom took me with her to visit him. It was a long trip, ten hours by propeller plane followed by landing in Baltimore due to bad weather and having to train up to New York City.

Somehow, I‘d gotten it into my kid’s brain that New York was full of bears, so I’d awaken early in Nan’s apartment, listening for bears, worrying.

We visited Pops in hospital. He played and joked with me while in a recliner bed. Nan took me to a park while my mother spent time with her father; her final visit with him, I think.

My mother went out one night and I was frightened she would not return, that the bears would get her. I cried and was overjoyed when she returned with a present for me: Plastic Martians.

Stomach cancer defeated Pops. My mother flew out for his funeral and returned to West Hollywood with Nan, ushering in a new era with my grandmother as built-in babysitter.

Standing upon a swivel to dust a high shelf, Nan fell and broke her arm. She called for help and, when my mother got there, we boys right behind, Nan called for smelling salts, a small glass jar with green goop she kept on her dressing table. I ran to get it; Nan took a whiff, came round. Then I took a whiff—and nearly passed out.

Nan’s arm was set in a plaster cast for about six weeks after which she resumed her household chores. One such task was washing dishes after dinner. And one of mine, which I alternated with my younger brother (who got out of everything), was to dry the cutlery. I’d ask Nan questions and she’d tell me stories about when she first met Pops.

The first time I smoked a cigarette—at age 12—was after seeing the movie Casino Royale with friends. I had to tell someone. I told Nan (my brother would have finked) while drying cutlery and she laughed, especially when I told her the brand: Bull Durham. That’s what Pops had smoked when she first met him.

It was sometime in 1968, when I was 14, that Nan first showed signs of paranoia. By then she had her own apartment nearby and was spending too much time alone. So she dreamt up an unknown terminal illness for herself, a symptom of which, she believed, was a strange odor. None of us could smell any such thing, but this only made her suspicious that we were part of a plot, hatched by her doctor, to keep it secret from her.

Next, she began to believe that microscopic bugs were infesting her.

“See, here’s one!” she’d holler. My brother and I would put it under a magnifying glass and find a particle of grit or dead skin.

In the summer of ’69, my family traveled to London for what was supposed to be a three-week summer vacation. But when the return flight arrived in LA, we weren’t on it; only my dad, who returned to sell our house and ship out the furniture. Nan didn’t know we weren’t coming back until, after setting the table for dinner, my father walked through the door without us.

The house got sold and Nan was left on her own, with no car since she never drove. My older brother remained in LA, at college, and he’d stop in to visit Nan. But without a loving family nearby to keep her mind at least partly anchored, her mental health deteriorated. Left on her own, Nan decided she wasn’t terminally ill after all. She concluded that there was an elaborate plot underway to kill her. Slowly.

Nan believed that while she was asleep one night, they planted a metallic device inside her stomach. Actual surgery, right there in her bedroom. Then they commandeered the apartment above hers and installed a giant magnet to control her movements.

I never figured out who they were, but I gather it had something to do with the Turks. Maybe she believed they were still trying to make Armenians extinct.

Arrangements were made for Nan to join us in London. I was part of the family delegation that met when shew flew into Gatwick Airport. Nan was ecstatic. She laughed deliriously about how she’d put at least 30 people out of work by pulling a Houdini; laughing about how they were scratching their heads wondering where she went. In a somber tone, she related how, only one week earlier, the side panels of a large truck were opened on the street in front of her apartment to release a cloud of poisonous gas, and it was a miracle she was able to close her windows in time to thwart the attack.

In London, all was well. For a few weeks. Then one day Nan announced that they had managed to track her down and had now arrived, madder than ever before, to finish the job. To accomplish their mission, they had commandeered several neighboring houses. The scenario, as her tormented mind fantasized, took a mean turn: She now believed we were part of the plot. We had to be, she un-reasoned, since we were so willing to stand by and do nothing while they aimed ultraviolet radioactive beams through her bedroom window. We all tried, of course, to convince her otherwise. But she refused to believe that her mind was making this up. After all, she’d point, she’d seen movies about this kind of thing. Movies like Gaslight.

To “prove” her point, Nan pointed out a streetlamp that glowed purple, different from the others, probably to recharge. She protected herself from such invasive tactics by sticking hundreds of pins and needles into her curtains—to “deflect the rays,” she said.

As relations with the family worsened, Nan would not come down for dinner but locked herself in her room. My mother would leave meals outside her door, but they went uneaten, presumably, to her thinking, poisoned. Instead, she would wait until everyone was asleep, then slip down two flights of stairs to the kitchen for cheese and crackers.

No one in the family wanted Nan to be committed to a mental health facility. But after a long six months, hoping in vain for her to snap out of it, there was no choice.

The family physician was summoned one afternoon to see for himself and make a determination, Nan was lured from the bedroom. She took one look at Dr. Cohen in the living room and bolted for the stairs. The good doctor had been hitherto reluctant to section her, but now he was convinced, and Nan was dispatched to Friern Barnet Hospital.

Next day my mother and I went to visit her. She was dressed in a cream-colored hospital gown and, when she saw us, begged us to take her home. She said everyone there was crazy, including her roommate, a black woman who practiced voodoo.

We visited Nan every week. She became more calm and at ease with her surroundings with each new visit. She had even made friends—something Nan rarely did in the outside world.

I was fascinated by the patients during my visits. I felt drawn to them. I wanted to stage a concert at the American School in London and donate the proceeds to Friern Barnet. However, my mother was aghast at such a notion because of the stigma back then attached to mind challenges.

Nan was tested with various meds. And zapped once with electroshock therapy. Can you imagine, strapping down and zapping with electricity someone who believed she’d been targeted by people who wanted to zap her? It boggles the mind.

After a few months, Nan was allowed home for weekend visits. And then one day she got discharged and came home for good.

Only once did Nan acknowledge her lapse from sanity. At the height of Nan’s paranoia, my brother wagered her five pounds sterling that she was imagining the conspiracy against her. One day, not long after she returned from Friern Barnet, Nan wordlessly pulled a five pound note from her purse and handed it to my brother.

Nan thereafter lived a quiet, unobtrusive existence of medication and television soap operas.

Through the day, she sat herself in a living room armchair and watched me—watched us all—come and go at a quick pace. To where, I have no idea any more. Wherever it was, it matters less than the stillness and silence she found. She once said, “You’re always in a hurry.” And she was right. I was always on the go, go, go, not understanding the importance of stillness and silence.

I could have, should have, stopped in my tracks, slowed down, sat upon the chair next to my grandmother and asked, “How are you doing today, Nan?”

But what matters now is… she isn’t here, and no, I can’t. And I sure wish I had another chance to make that right.

We boys grew up, married, had kids and lived nearby. Our wives grew to love Nan, and we all stopped by frequently to visit her. Nan’s most memorable line during this era was, “Cup of tea?” She brewed the finest cup in the world.

My daughter, as soon as she could talk, dubbed her “Big Nan,” and the name stuck. Soon, all of Nan’s great grandchildren called her Big Nan. And Big Nan’s eyes would twinkle whenever any of them were around. She would brew the toddlers mild tea and sneak them extra chocolate chip cookies.

I was always moving to and fro, crossing the Atlantic and back again, living on both sides. But Nan was constant, an anchor in my life. She was always home to welcome me with a cup of tea no matter where I had been or for how long. I’d walk in, jet-lagged and exhausted from flying coach and inhaling second-hand smoke, put down my bags. And Nan would say, “Cup of tea?”

Then one day I hightailed out of London to set up a new life in the USA, a self-imposed exile after earning parole from my family’s business. I didn’t think for one moment I’d never see Big Nan again. She was 85 and strong as an ox. No one doubted she’d outlive her Uncle James, who lasted over a century. (Those Armenian genes….)

We hugged near the front door, taxi waiting, a kiss on each cheek. And Nan blurted, with uncharacteristic emotion, “I’ll miss you!” And as she said goodbye to my wife, and to my daughter, she looked ready to do something I’d never seen her do before: She looked like she was going to cry.

When the clanging of the telephone woke me at six a.m., I picked up the receiver with a sense of foreboding. The satellite static crackled during the two seconds it used to take for a trans-Atlantic call to connect. And then my brother’s voice. His words came slow. “I’ve got some really bad news.” He paused a beat. “Nan died.”

I returned to London for her funeral and slept in my old room in my parents’ house. Returning home did not feel the same without Nan there, offering a cup of tea.

I couldn’t sleep but lay on my bed, gazing out the window at the purplish night sky. Then I saw something I’d never seen before, something I had always wanted to witness: A shooting star.

Synchronistically, only two weeks before, browsing a book at Bhodi Tree in West Hollywood, I read that a shooting star signifies the death of a grandparent.

I’ll always believe that what I saw in the sky was Nan’s farewell.