This column appeared in the Santa Barbara News-Press in October 2021.

The distinction between a column and news reporting is that the former incorporates voice and style, perhaps a smattering of opinion; the latter should be “just the facts, ma’am,” though you wouldn’t know it these days because so much journalism that masquerades as “reporting” comes with an overdose of spin-oriented adjectives and adverbs.

My investigative columns are the result of many influences, starting with the Sunday People, where I cut my teeth as an investigative reporter over 40 years ago.

Two men—Investigations Editor Laurie Manifold and his deputy, Alan Ridout—each week produced two full pages of investigative stories (sometimes just one big one) under the banner Man of The People Investigates.

They worked five days a week (Tuesday through Saturday) investigating four-to-five stories at any given time. Their unit was autonomous from the newsroom to protect sources and stories (shared only with the newspaper’s editor), supported by an odd assortment of freelancers “doing shifts.” (In Britain, newsrooms were understaffed, thus freelance was a perfectly acceptable way to practice journalism, unlike in the USA where freelance is often considered a euphemism for unemployed.)

Every week the Sunday People investigative page exposed villains and conmen, sex scoundrels and scammers. In its heyday (1950s and ‘60s) it exposed some of the most dangerous gangsters in London’s East End.

I got into journalism investigating and writing about the Bilderberg Group. But my break into big time (Fleet Street) journalism came when I infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan.

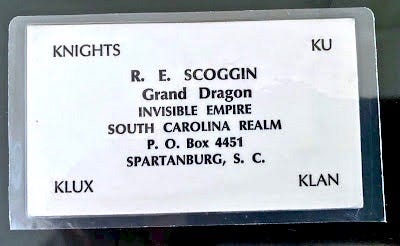

It began with a tip that the Grand Dragon of the Invisible Empire, Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in South Carolina, desired to establish a “klavern” (Klan-speak for branch) in Britain.

Posing as a wannabe Klansman, I contacted Robert E. Scoggin (the Grand Dragon who doubled as Imperial Wizard) by phone. We engaged in a lengthy chat during which he determined that I should be his main facilitator. He then proceeded to recite to me the names and phone numbers of prospective Klan members from all around Britain.

I took what I had to the Sunday People.

They bought it for a good chunk of change and put me to work for them.

Guided by the pros, I made contact with those on Scoggin’s list and invited them all to a hotel room near King’s Cross, one of London’s main train stations. The room was wired with microphones, add a photographer with telephoto lens who clicked away as our targets—about a dozen—came and went, including a thuggish family (a father and two sons) who claimed to possess an arsenal of illegal guns. They talked of wanting to abduct inter-racial couples to tar-and-feather them. They were an ugly bunch.

We had our story—a good one.

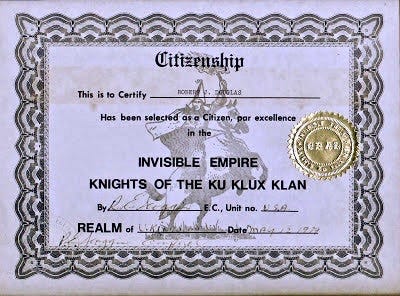

But it got even better when Grand Dragon Scoggin, learning from me of our “successful” meeting, invited me to visit him in Spartanburg, South Carolina for the purpose of being “naturalized” into the KKK.

Naturalized?

“You can’t run a branch of the Klan,” he drawled, “until you’re initiated in a ceremony.”

The editor of The Sunday People agreed, so off we went—me and Alan Ridout plus Angus Mayer, a freelancer who was brought in to assist.

First thing, after klansmen collected us in their van at a Days Inn motel on the outskirts of Spartanburg, they hit us for “dues”: Twenty bucks each.

After arriving in front of Scoggin’s ranch house—pickup trucks parked everywhere—we were escorted into a dark garage pointed up its narrow, creaky stairway.

At the top, a door opened and there, standing before us, was the Imperial Wizard, decked in a gold satin robe and cone-shaped hat. On the walls of his den hung blacklight posters glorifying the KKK, boldly illuminated with ultraviolet light.

In the center of the den: An altar with a Holy Bible opened to Corinthians 12.

The room then filled with about two dozen Klansmen (and women) wearing white robes, fully hooded. They formed a semi-circle around us and the thirty-minute ceremony began.

Scoggin anointed us with holy water and tapped our shoulders with the flat side of a sword—rendering us knighted into the secret fraternity of haters.

At one point, the Imperial Wizard pointed to a snakeskin nailed to the wall and said, “That’s what happens to traitors!”

The lights came on, hoods were removed, donuts and coffee served.

And someone produced a tape measure.

Why a tape measure?

Bespoke robes and hoods of satin were to be hastily tailored for us. Not normal white ones, mind you, but red robes, which identified us as “Kleagles” (Klan-speak for “officers”), pledged to run the UK Klavern.

That’s not what happened, of course.

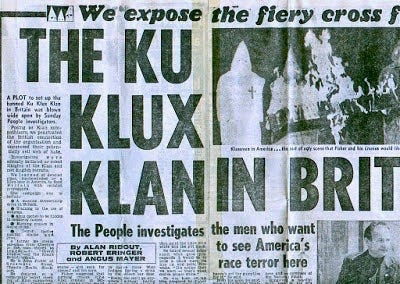

No, what happened was this: Two front-page, center-spread stories “splashed” (Fleet Street lingo) over two successive Sundays exposing names and photographs of those who desired to bring hate to Britain.

It blew the UK KKK out of the water.

Literally. That was the end of the KKK in Blighty.

And, tipped off (by me), Special Branch (police) raided the home of thuggish father and two sons, found the guns of which they spoke—and confiscated them.

One anecdote of that experience stands out above all others:

On our final day in South Carolina, the Imperial Wizard took us on a tour of the Blue Ridge Mountains leading, that evening, to a “Tri-State” KKK rally across the border into North Carolina and a field reached only by a single lane gravel road. Sitting bumper-to-bumper in a long stream of vehicles, I noticed a state police roadblock up ahead—and could see that the state trooper was asking each driver for ID.

Problem: The only ID I had was my UK driving license—in my real name, not the alias I was using for Bob Scoggin, who was sitting in the passenger seat next to me.

My turn came.

The trooper leaned in. “Driver’s license and car papers,” he drawled.

I opened the glove compartment and handed him the car rental agreement.

“I said driver’s license,” he repeated.

“It’s in the trunk,” I said.

“Well, go get it.”

I got out and walked around the car, followed by the state trooper.

And then—uh-oh—Scoggin got out too and met me around the other side, stood beside me as I rifled through my duffel bag, mind racing about an escape ramp if Scoggin discovered I wasn’t who I said I was.

But there was no escape route. And I recalled Scoggin’s snakeskin nailed to the wall: That’s what happens to traitors!

Just as I was about to produce my license, Scoggin extended his right arm in front of me and offered to shake hands with the trooper. “Hi, I’m Bob Scoggin, Imperial Wizard for South Carolina.”

The trooper smiled, shook Bob’s hand then drawled, “Well, why didn’t you say so? You boys go right on through!”

Minutes later at the rally, our newly tailored robes were provided to us.

Over the next few years I infiltrated violent anarchist cells and neo-Nazi organizations for the Sunday People. It became a specialty of mine, infiltrating hate groups and reporting on their activities from the inside.

This kind of undercover journalism was an accepted practice in Britain, but only as a last resort for getting the story on evil-doers, based on the principle that if a particular entity was presumed to be doing bad things and no one involved would talk about it to an outsider, it was ethical to penetrate them to get at the truth.

Another early influence was Paul Foot, who wrote an investigative page for the Daily Mirror, another Fleet Street newspaper.

Paul was known as a “campaigning” journalist, which meant he was forever on a crusade to expose evil and change society for the better—and urged readers to send tips “I ought to investigate.”

And then there was Nicholas Davies, the Daily Mirror’s dapper foreign editor, who could digest an extremely complicated international situation and distill it into a mere 150 words that would explain everything in a way any layman reader could understand.

A fourth influence appeared when I settled for a time on the Jersey Shore and read the Asbury Park Press. This daily newspaper ran a twice-weekly column called Trouble Shooter. Readers would write the anonymous columnist and seek assistance to settle a dispute with a merchant. Trouble Shooter would do so—and publish the results.

That was interactive journalism before the internet.

Finally, there was the Weekly World News (little sister to The National Enquirer) and a columnist by the name of Ed Anger, obviously a pseudonym, who ranted and raved with opening lines such as “I’m madder than a zombie with a mouth full of Biden’s brain.”

That influence, too, found its way into the nether-reaches of my mind.

without a shadow of a doubt, You have led a most interesting and exciting Life, Robert, It is amazing to me that you have been able to cram so much diveersity into one liftetime, and I hope that you are able to continue to do this for many more exciting years !!

ATB, AKJ in WA