This story is about a trip I took to Oslo, Norway, in September 2013, to pay homage to the artist nicknamed “Bizzarro.”

1.

“You have no idea what we’re getting into,” I say to Van Stein as we board a jet to Oslo. “We are about to descend into the depths of despair, melancholy, anxiety, depression and total helplessness.”

Van Stein is an artist; I am a writer. Depression and helplessness should come naturally.

By this time, we’ve traveled together for over ten years exploring creativity and madness, which lately had been exploring me—mostly, paranoia, on the basis that people truly are out to get me.

From afar: For exposing the secrets of a country and its inept ruler.

Up close: The unwelcome attention of a psychotic old hippie bent on acting out his obsession with me by stalking, glaring, cursing and staging theatrical exhibits outside his house depicting my death by arrows decapitation.

On top of all that, I’m in need of an Internet detox—or de-charge.

What finer zone, I reason, to rediscover non-virtual reality than the purity of the Norse.

I’d been planning such a trip, or stressing up to it, for almost two years, after reading a biography of Norway’s best-known artist, Edvard Munch (pronounced moonk).

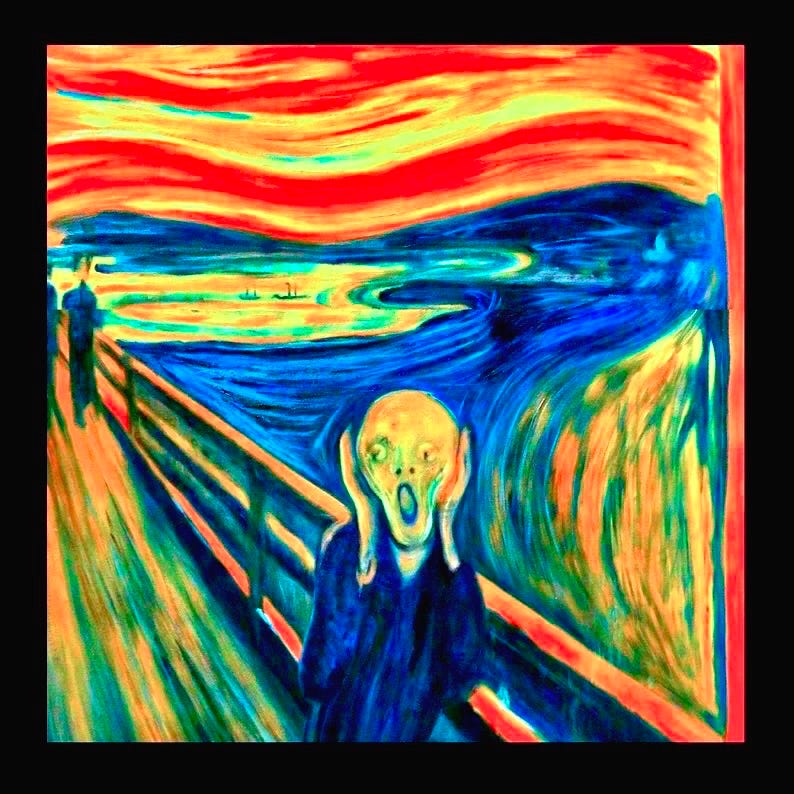

Munch painted Scream, one of the world’s most iconic paintings.

Munch bared his soul in his art, ensuring that those who view his paintings actually feel the anxiety and despair he felt.

His own words: For as long as I can remember I have suffered from a deep feeling of anxiety, which I have expressed in my art. Disease, insanity and death were the angels that attended my cradle, and since then have followed me through my life.

Back then, there was no Valium or Xanax. Only alcohol. Munch drank a lot of it.

He felt as he painted, painted as he felt.

It had not been done before.

Many who viewed Munch’s paintings could not deal with his honest emotionalism. For most people in the art establishment, and in general, it was just too unnerving—and highly disturbing.

Munch did not care. He knew what he was doing—and why. And he also knew he was a great artist.

A plan to see and feel Munch’s work lingered in limbo until, spontaneously, it erupted in early September 2013, timing coincident with fortuitous relevancy: Munch painted his first Scream after becoming overwhelmed by a scream of nature inspired by a bloody red September sunset.

Furthermore, we would also be present for a full moon, thus satisfying our luna-seeking criteria, or, as Van Stein puts it, “We moon business.”

And, unbeknownst to me until after I bought a ticket, Oslo was in the midst of celebrating Munch’s 150th birthday with special exhibitions of his work.

Van Stein, having travelled with me on surreal adventures involving dead artists and writers, mustered, mobilized and now lay horizontal in a cubicle next to mine on Virgin’s Upper Class, hurtling through the night to London for onward travel to Oslo; a blur of a day in transfer and motion—a day erased, already into the next night when we descend into "that strange city [wrote Knut Hamsun, another notable Norwegian) no one escapes from until it has left its mark.”

I take a photo through the window and, inspecting the image on my screen, I’m astonished to find the full moon contorted into the shape of a heart—a message from Munch.

A case of Moonacy, perhaps. Just right for the mission at hand.

We descend, land and disembark onto a mobile stairway into the open air: cool, brisk and pure. I steel myself for Munch’s abyss.

Inside the terminal we are greeted by a gigantic poster of Scream.

Here we go, I incorrectly deduce: The commencement of crass commercialization.

Then: Immigration.

“Why do you come to Norway?” a border guard demands of me.

“Munch.”

He narrows his eyes, flicks through my passport. “You travel a lot?”

“Used to.”

“How long you stay?”

“Depends on Munch.”

He stamps my passport, a bemused expression.

Just beyond Customs, Tom the Driver leads us to his BMW and, within seconds, we careening into a clean smooth highway, gliding toward a city glow—signs saying Sentrum—until we arrive at its epicenter: Karl Johan Gate, featured prominently in many of Munch’s paintings.

And then its nucleus: The Grand Hotel.

We check in, dump our bags, elevate to Bar Etoile on the roof.

It is midnight, though our bodies think it’s teatime.

The solution is simple: Chablis.

A glass of Chablis costs $30 in the world’s most expensive city.

But at this hour, in this place, it is worth every penny.

At one a.m. the bar closes.

We descend to the lobby and wander outside.

An attractive East African woman approaches us. “Fokken?” she asks.

Jeez, we’re chic magnets in Norway!

“Not tonight, sweetheart, but thanks for asking.”

Clusters of other such ladies huddle at street corners, assessing our intent, amused by our travel hats: Van Stein sports an Australian Akubra; I, a felt fedora from Lock & Co with a leather and turquoise hatband I acquired in Aspen, Colorado.

“Cowboys!” hollers one of the smiling street women.

East African men (Somalis, I later learn) lurk nearby, pimps or drug dealers, maybe both.

“Are you okay?” one of them calls to me.

Meaning: Need any meds?

He couldn’t guess I’d brought my own cornucopia. “I’m good, thanks.”

Van Stein and I continue trucking down Karl Johan Gate.

A church clock on high strikes two.

“When I bought my bar,” I explain to Van Stein, “my bookkeeper, who also owns a bar, told me, ‘Nothing good can happen between midnight and three in the morning.'”

The night grubs are still grubbing, proliferating, as we traverse back to The Grand.

2.

After five hours sleep, Van Stein and I are no longer operating in real time but in surreal time; the bounce, we call it. Surreal Bounce.

There is Munch to do; he is everywhere in Oslo.

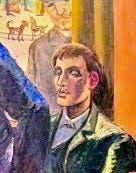

First, breakfast in the Grand Café beside a large mural depicting café society as it was in 1879.

One of this mural’s inhabitants is Munch—zoned, by the look of him, having enjoyed, one understands from research, several drinks before breakfast.

We load up on protein: freshly cooked omelets with everything, sides of baked beans and smoked fish.

Tom the Driver arrives at precisely 9:03 and we order him to a quaint zone called Grunerlokka. This is where the Munch family settled in 1875 when Edvard was 12— specifically, Thorvald Mayer’s Gate (the main thoroughfare) and Number 48, Munch’s first of five homes in this neighborhood,

The ground floor is now Palazzo Pizzeria; the architecture has not changed.

Newly built when Munch arrived, Grunerlokka was back then considered the “wrong side” of the river. Overcrowded, its poverty welcomed tuberculosis, cholera and polio and, consequently, was rife with sickness and death.

Today, Grunerlokka is Oslo’s trendiest place to live: home to artists, writers, musicians and bohemians, with the sort of hip bars and cafes that cater to rebellion and free spirit.

At this time of morning, Grunerlokka is quiet; bohemians and artists are, by nature, a late-night bunch.

We pause, absorb, focus and snap photos among locals who seem bewildered by our mission and amused by our enthusiasm.

After two years, the Munch family moved elsewhere in Grunerlokka, to Fossveien, first at # 7, then # 9, then # 4 Olaf Ryes Plass, now painted a pretty purple, overlooking a park.

And finally, Munch’s last home in Grunerlokka: Schous plass 1.

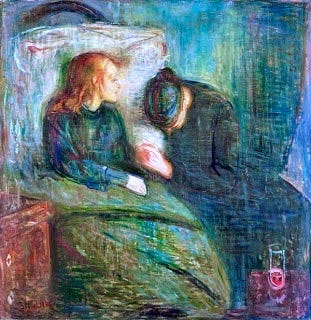

This is where he painted The Sick Child—his breakthrough work as an artist.

Today this building houses a coffee bar called… Edvard’s.

Inside, Scream covers a whole wall.

Van Stein and I savor cappuccino, and the moment.

Next door, an artsy shop displays plaster Munch death masks. I want to buy one, but the shop is closed (and remains so throughout our visit).

Bohemians, by nature, do not keep regular hours (or days).

But unlike Arles in France, which peddles Van Gogh on every street corner (and in between), and Figueras in Spain, which celebrates Dali with trinkets made in China, Munch is not widely marketed in Oslo.

On the contrary, there seems an indifference to Munch, as if the natives merely tolerate his renown.

Perhaps they do not like to be celebrated for anxiety and despair, alcoholism and insanity.

Van Stein and I hop back into Tom’s car.

“We need to go where Munch is buried,” I say, handing him a printout from findagrave.com.

In all the years Tom has shepherded visitors around Oslo, no one has ever asked him to see Munch’s gravesite. And until our arrival, Tom did not even know where Munch is spending eternity. He shakes his head good-naturedly. He already understands we are not his normal tourists.

The Cemetery of Our Savior is just across the Akerselva River, once the divide between wealth and poverty, good health and bad.

This exclusive graveyard is the final resting place for notable Norwegians.

Perhaps from stress brought on by the Nazi occupation of Norway, Munch succumbed to the bronchitis (in 1944) that plagued him most of his life. He believed that the Nazis, who labeled his art degenerate, would find and destroy his paintings—his "children." (To his horror, they had done this in Berlin.)

There are no directions in this cemetery, and though it is not vast, it is not small. It is serene, however, with rolling hills and quietude.

Tom enquires from someone who, though alive, belongs to this graveyard.

The best our driver can discern is that Munch is out there, and we try to follow the caretaker’s point, ambling among the dead, inspecting inscriptions.

Finally, I come upon Munch’s head in bronze atop a five-foot monolith. His bust wears the same expression as the masks in the window display of the artsy shop next to Edvard’s coffee house.

“I knew it,” says Van Stein. “They must have come here late at night to make a mold.”

We pose, Van Stein and I, for a photo with Munch. And I leave a wooden nickel (good for a free beer at my bar) on the cement slab covering his bones.

The graveyard brings to mind mortality, which I do not fear. Instead it cheers me that I am here, alive, living this moment.

“You might as well enjoy the time you’re here,” I say to Van Stein while meandering back to the car. “Being alive is just a drop in the bucket compared to how long you’ll be dead. And it’s coming faster than you think.”

“How’s that?

“You’re over 50 now. Going from 49 to 50 is one-fiftieth of your life. You know how long it seemed to get from 4 to 5 years old? That’s because going from 4 to 5 was one-fifth of your life. Time is relative. But I wouldn’t worry about it,” I add.

“Why not.”

“Does it bother you that you weren’t here for billions of years before you were born?”

Van Stein shakes his head. “Why should it?”

“Exactly. You won’t even know when you’re not here for billions more.”

3.

“Where is the nearest mental hospital,” Van Stein asks Tom.

“Like everything else,” replies our driver. “Ten minutes away.”

“Can we go there?”

“Now?

“When else?”

Tom shrugs—a hint of trepidation.

Ten minutes later we pull into an austere estate.

“This is it,” says Tom. “Gaustad.”

Gaustad is the asylum Munch’s sister called home. Laura’s condition caused Munch much anguish. He would visit her here.

The brick buildings are somber, as much from age and dampness of a northern clime as the heartache they’ve witnessed.

Van Stein and I walk around, snapping pictures, expecting any minute to get thrown off the property.

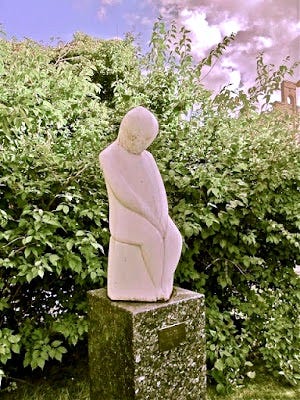

A sculpture catches my eye.

It is small and simple and sits upon a marble pedestal. The naïve human form represents both genders, head bowed, hands tucked between its legs.

A brass plaque identifies its name: Sorrow.

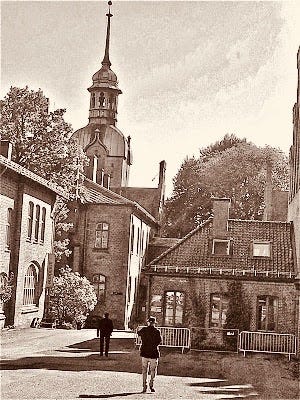

From behind, we arrive at the main entry forecourt.

“This is the first thing arriving patients would see,” whispers Van Stein, pointing at a clock tower crowned with a church-like steeple, set behind a ten-foot black iron gate with a large lock.

“With a welcoming committee, inside.” I add.

Tom the Driver sidles up to us. “Would you like to see inside? They have a private museum. I can ask if they’ll open it for you.”

A few minutes later, Tom beckons us forward.

Is this a trap? Van Stein and I exchange nervous glances.

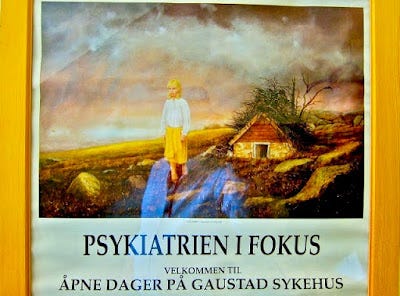

A poster near the door of the museum features a painting of a landscape with clouds at sunset and a sole figure, a pretty, young blonde female (the artist, presumably), lost in her mind, or out of it. Behind her, a cottage is half buried in the ground.

Beneath the image, these words: Psykiatrien I Fokus.

'“Yup,” I say to Van Stein. “The mind is a terrible thing to lose. But psychiatry fokus us real good.”

We descend to a lower ground floor.

Tom guides us in, glances around apprehensively. “Gives me the creeps,” he mumbles.

Van Stein and I are in our element as we stroll through a large room housing two patients on gurney-style beds.

Van Stein leans in on one. “Jack, that you?”

Indeed, the wax figure looks remarkably like Jack Nicholson after his lobotomy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

A side table features vintage electro-shock equipment.

Nearby sits a display case of lobotomy instruments.

“I think I’d prefer Prozac and Abilify,” I say.

Another room is Memory Lane, featuring photos of lobotomized patients’ past, along with some of their personal belongings, such as shoes and spectacles.

From the look of these portraits, they too might have preferred Prozac and Abilify.

4.

The sun is scheduled to set at 7:26 p.m. and a full moon to begin its rise at 6:58.

Ekeberg’s location, on a hill facing southwest, is not ideal to view a moonrise. But with weather conditions potentially changing from balmy and light cloud to overcast and rain, we have to grab grab the sunset while we can.

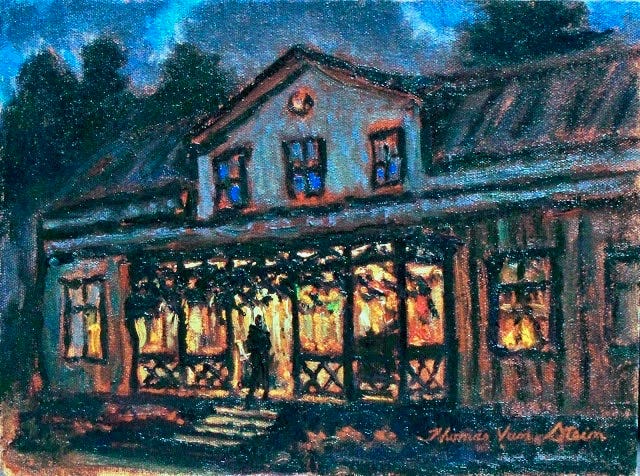

Van Stein has chosen the terrace at Ekeberg Restaurant for his painting. He erects an easel and preps his palette while I order us a round of ice cold Aquavit: a thick, amber, anise-flavored libation indigenous to the region.

The sun sets slower (or seems to) in the northern hemisphere. This works to Van Stein’s advantage as he knocks out a small sketch in oil before proceeding to a larger board before the sun sinks below the horizon.

He paints freer than usual, an explosion of color.

I comment on this.

He mumbles something about The Munch Museum unlocking something.

I order us sandwiches of Parma ham and cheese—and more Aquavit.

Feeling refreshed, and tight, we return to the Scream site.

Van Stein photographs me standing where Munch’s screamer stood. Inexplicably, I appear phantom-like.

When he turns his lens the other direction, the artist catches me amid Orb Storm and Moon.

Orbs are translucent balls of white light that appear in digital photography, usually in graveyards, cathedrals and haunted houses. Some people think they represent ghosts or angels; others believe they are aliens.

Many scoff at such a notion, unwilling to accept another dimension—or anything that challenges their mechanist belief systems.

In our arrogance as humans, most of us believe if we cannot perceive something, it must not be there. Yet digital photography is able to discern a phenomenon (we’d call it supernatural) that the human eye cannot capture.

5.

The Grand is fully booked for the weekend and orders us out.

We soon discover that every hotel in Oslo is fully booked.

Could Munch be that big a draw? (No, it was a marathon.)

I have a Norwegian friend I’d never before met, but we’d talked on the phone and e-mailed one another, and, very graciously, she expressed a desire to host Van Stein and me during our visit.

Acceptance of such hosting becomes essential, as our only other options are sleep on park benches or, as I suggest to Van Stein, board the evening ferry to Copenhagen and allow chance and destiny to dictate thereafter.

Copenhagen would have been my choice, if only to avoid surrendering independence. But sometimes you’ve got to give up something to gain something.

Before vacating our rooms, the artist and I stroll down to the harbor. People in dark clothing on the streets look to me like a series of Munch paintings.

An Oslo thing—or my new reality?

It seems odd that the world’s most expensive city is without the high-end shops that strategically situate themselves among wealth: No Gucci, no Prada, no Cartier. No Hermes, no Louis Vuitton.

The shops are all native, perhaps to preserve purity. Aside from traditional lusefafte (heavy wool cardigans) and plastic trolls, there is nothing interesting to buy.

All I’m looking for, anyway, is a talisman. Something to carry at all times to remind me of Munch—an antidote, perhaps, against anxiety, despair and depression.

At a jewelry shop called David-Andersen (no Tiffany here), I come upon a sterling silver nail file.

Symbolic? As a kid, I relentlessly chewed my fingernails.

But I’m not convinced.

On our return path from the harbor, we pass a precious metal company called K.S. Rasmussen, whose display window contains silver ingots.

We carry on.

A block later I stop in my tracks, having experienced an epiphany of sorts. “That’s it,” I say to Van Stein. “Let’s go back.”

I ask to see Rasmussen’s 100 gram silver ingot.

It is soft with rounded corners, a pleasure to hold, to clasp my hand around.

My search for a talisman is over.

The clerk, a middle-aged woman, tries to talk me out of it. “We have to charge 25 percent premium on silver ingots,” she says.

“Really? I’ll take it.” I remove the ingot from its wrapper and place it in the palm of my left hand, feel its power soothe my soul before slipping it into my pocket.

From this moment, whenever I feel anxious about anything I pluck the ingot from my pocket, as some might handle a meditation stone or rosary beads, and appreciate that I am here and I’m okay.

“Where are you going?” asks the cheerful check-out clerk at The Grand’s front desk.

“Maybe a park bench because you’re kicking us out,” I say, “but thanks for asking.”

“Well, have a nice day!”

(At least everyone speaks English.)

Tom the Driver is on hand to stow our bags and kill time before we’re due to meet our host.

I suddenly realize we have not yet seen Engebret, the oldest café in Oslo and headquarters for the Artists Association, to which Munch belonged—until Engebret 86’d him for drunkenness and accusing a server of stealing his scarf and gloves.

We alight at a cobblestoned square in the old-town.

Engebret has changed little since Munch was allowed inside. Standing in the room where the artists met, it is not hard to imagine the drinking, the exchange of creative ideas, the madness.

Tom the Driver points across the cobblestones from Engebret to the Museum of Modern Art.

Van Stein and I bound over to see what Norwegian artists have been doing since Munch.

Inside, it is not about painted canvas.

It is about distortion and turmoil—and very disturbing.

In fact, scarier than what we saw at the insane asylum.

I cannot stand it. Literally. I have to leave. I reach for my new talisman and beat a hasty exit.

“It is Munch’s legacy,” says Van Stein, later. “Munch’s paintings were unnerving to people in the late 1800s. He has given his permission to the newer generations to exhibit their insanity. I think the point of these modern artists is that things are not always nice and pleasant. I call it what-the-fuckism.”

As previously mentioned, I met our host through e-mail, which led to telephone conversations, which finally led to this in-person rendezvous.

Her unexpected appearance in my life pertained to my past intelligence work.

She shall remain the mystery host because that is how she prefers to live: a simple life in the country.

The countryside—and Sweden is no exception—harbors many secrets. This part of Sweden, near the Norwegian border, is considered a grey zone due to its history of partitioning. The people who sparsely populate it are mostly anarchists.

It is the perfect hideaway.

6.

Returning to Oslo, and The Grand, it is time to wind down.

I meet Van Stein in the Grand Café bar, our final night in town.

A bottle of absinthe catches my eye. Pere Kermann’s.

This is what Munch would have drunk.

I order a nip, as Munch called it.

Sadly, this bar does not possess traditional absinthe paraphernalia. No perforated spoon.

Furthermore, the bartender does not even know I need a sugar cube and small jug of water.

Improvising, we toast the Green Fairy, and Munch.

Suddenly, a rosy glow fills the café.

We step outside to marvel the sunset.

I snap a photo, inspect it; something odd catches my eye. I zoom in, snap another pic and show it to Van Stein.

“Tell me you don’t see what I see?” I say.

Incredulous, Van Stein then captures the specter on his own camera: a highly defined, distinctive face.

The specter’s mouth is wide open, as if… screaming.

In awe, we return to the bar, our absinthe.

Then we grab a table and steady ourselves for the special “150th anniversary Munch Menu.”

First course: Grilled scallops, petit pois, fried rye bread, and mussel foam.

Second: Chateaubriand with herbed butter and scalloped potatoes.

Third: Chocolate éclair filled with vanilla cream.

This was Munch’s meal of choice, for which he would try—usually in vain—to barter his paintings.

After dinner, I raise my camera to snap a photo of the ceiling over Munch’s favorite table, near the window.

Upon my digital screen, an unusual orb is clinging to a lightbulb.

Munch saying hey?

Maybe. Who can truly say for sure?

I retire early with a 6:45 a.m. alarm-call.

It comes at 2:33. Karaoke from a bar down the street.

The croakers aren’t singing, they’re screaming.

Screaming at the moon.

It is their therapy.

Lesson: If you cannot create art to quell your madness or depression, there is always karaoke.

Munch’s torment and enemies (real and imagined) pushed him to succeed—and to quell his angst and depression through art therapy.

Oslo’s mark on me: a realization that paranoia is fine, as it pertains to genuine enemies.

Says my brother, echoing a Chinese proverb: Your worst enemy is your best friend.

Meaning (as Nietzsche put it): You need formidable enemies to keep you sharp.

Or, says a sign in the Baltimore saloon where Edgar Allan Poe drank his final drink: Dry your tears and soldier on.

No one needs to pay a therapist 200 bucks an hour for years of analysis.

They need only do their art.

And if artless, scream at the moon.