September-October 2001

Berserk-ness begs company. So I phone Floater in Chicago, a call to departure.

“I need to go berserk,” I tell him.

“They found you?”

“No. It’s got nothing to do with them. I’m going where berserk was invented. You in?”

“Sure. I haven’t been berserk for a long time.”

“I’m serious.”

“You’re never serious. You’re the inventor of L.Q.” Floater knows my rule about undercover assignments: If it doesn’t have a high Laugh Quotient, I won’t do it.

“I am about this.”

“Okay, I’ll be serious, too,” says Floater. “How do we go berserk?”

“Iceland. In January.”

“You are crazy.”

“That artist you met? He’s coming too.”

“You’re both crazy. Sounds like I should be there—to keep you both out of trouble.”

*****

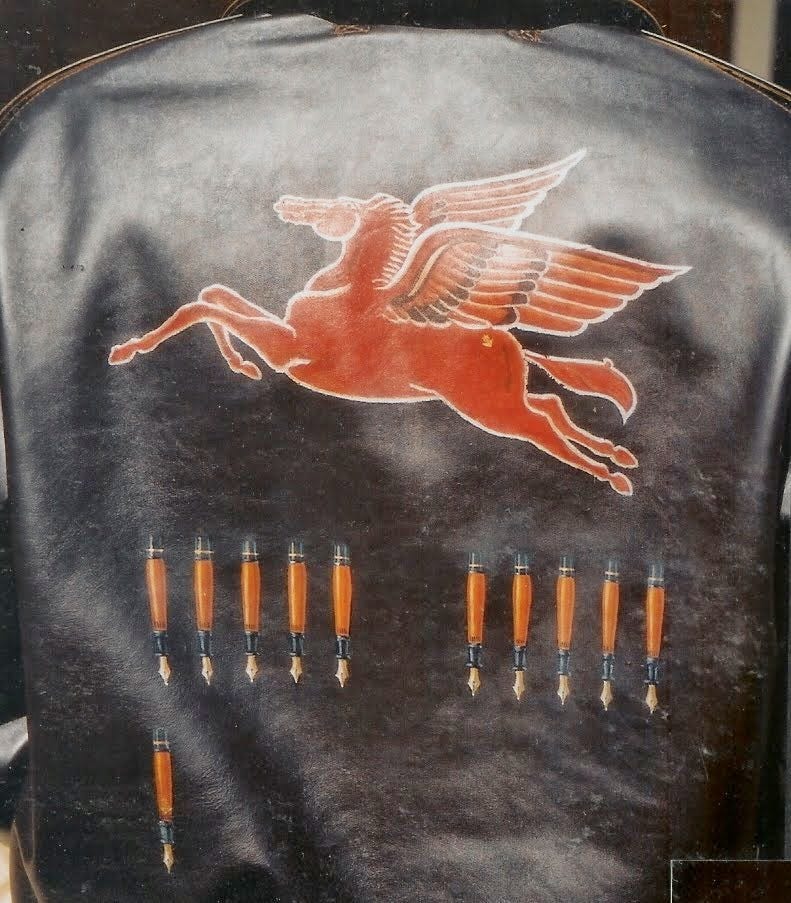

Van Stein and I laze on garden furniture in the courtyard outside Pierre LaFond in the Upper Village, drinking coffee, discussing what he should paint on my A-2 bomber jacket, just arrived from Eastman Leather in Britain,

Both of us lost a maternal uncle to WWII, both flyers. On his jacket, Van Stein painted an image of his mother, taken from a P-38 Lightning: Batlin’ Bet.

My uncle captained a B-24 that perished over Burma on February 29th, 1944. We settle on his plane, Pegasus, in my uncle’s memory.

“What about notches?” asks Van Stein. “Flyers put them on to represent missions. Some people go for bombs.”

“Nah. My missions are not about blatant explosions.”

“What are they?”

“Subtle stirrings.”

“Okay, so how about this?” Van Stein sketches a grouping of martini glasses.

“No olives?”

Van Stein sketches olives on a cocktail stick.

“Better idea.” From my back pocket I pluck a Mont Blanc Hemingway ballpoint pen—first in their Writer’s Edition. “This represents my missions. Can you do it?”

Van Stein is already sketching. “Piece a cake. How many do you need?”

I count my fingers. “Eleven.”

“Odd number.”

“Odd missions.”

“Dare I ask what these missions were?”

“Asking is easy,” I say. “It’s the answering that’s problematic.”

*****

The painted A-2 is ready a week later for my birthday in October, when Floater and Reek Pisserin fly in, the latter from London. I want to mark the passing of another year with my best friends around me, at Lucky’s, an aroma of seasoned pine as Montecito evenings turn chilly.

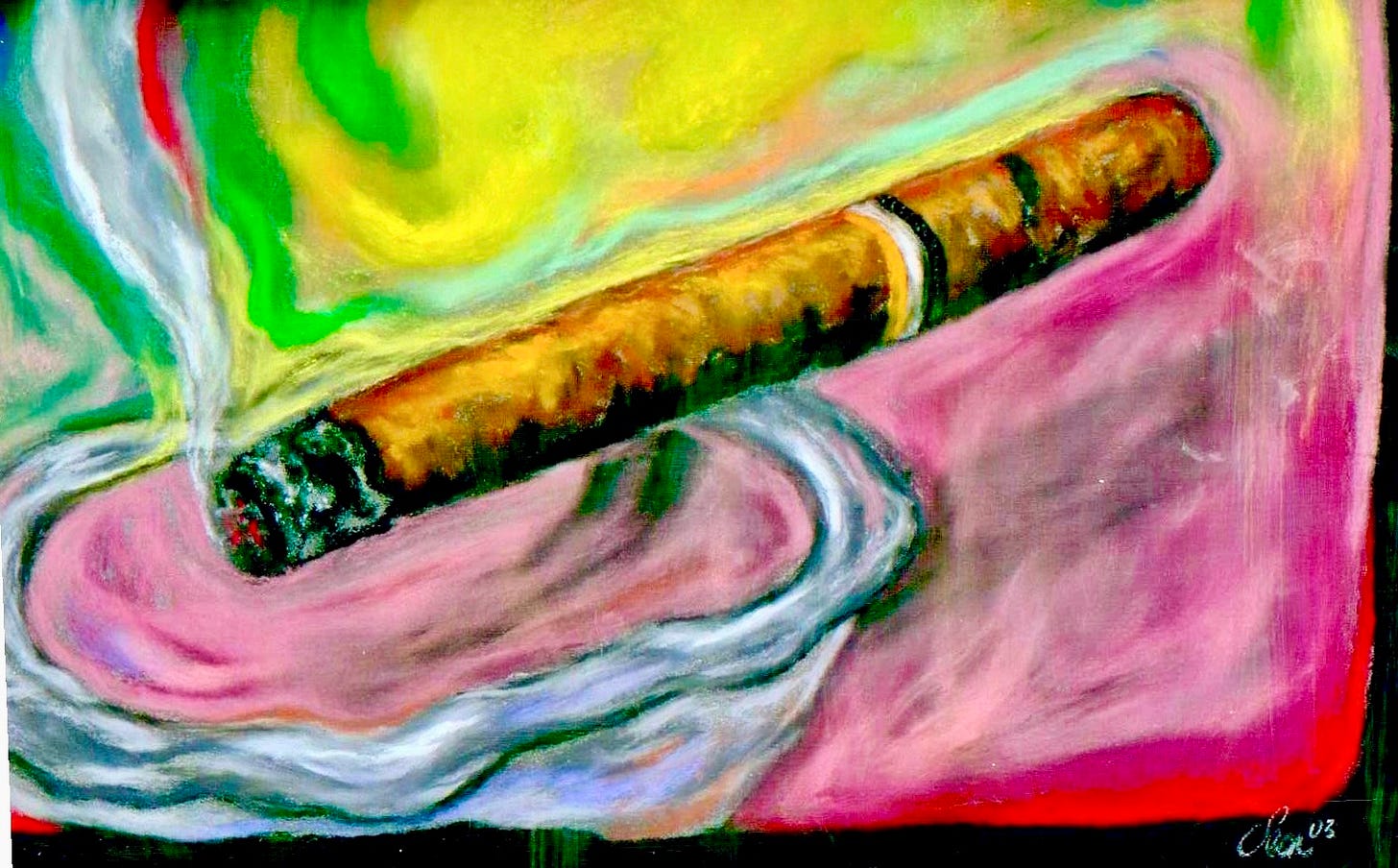

We lounge on the front patio beneath a pair of palm trees, smoking Cohiba cigars, sipping martinis.

Peter Noone walks by, says hey, exchanges small talk with his fellow Brit (Reek), and walks off.

“I see,” I say. “It’s okay for celebrities to approach us, make conversation, but we’re not allowed to talk to them.”

“So what do you do?” Van Stein asks Reek Pisserin.

The Englishman hems and haws. Finally he comes clean. “I’m a private eye.”

“I knew it!” Van Stein howls. “You’re all spooks.” He looks around, lowers his voice. “Sorry. But what are you doing here?”

I wink at Floater and puff my cigar. “We didn’t want to get into it so soon. But you brought it up, so here goes. We’re here to recruit you.”

Van Stein is chewing an olive. A sliver of red pimento dangles from his lower lip before he slurps it in, better than spitting it across the table, like last time. “For what?”

“An assignment.”

“What kind of assignment?”

“We need you to paint a nude woman playing a violin.”

“What woman?”

“Doesn’t matter. Young. Good-looking. Nice figure—you do figurative work, don’t you? And she’s playing a violin.”

“When?”

“After we visit the Lights of Marfa.”

“The what?”

“You don’t know about the lights?”

Van Stein shakes his head.

“They appear out of nowhere,” I say. “Dancing lights, in the West Texas desert. Near Marfa. Perfect for a nocturnal artist such as yourself, they illuminate the night sky over the Chihuahua desert.”

Van Stein pulls out a stick of dry vegetation. “We need to celebrate.”

“Are we supposed to smoke that?” I ask.

Floater looks around nervously.

“Nope,” says Van Stein. “It’s supposed to smoke you.”

“Excuse me?” Reek Pisserin, jet-lagged, isn’t sure he heard right.

Me too, for that matter.

“It’s sage,” says Van Stein, as if that should settle it.

“You’re going to cook ravioli with cream sauce?” asks Floater.

“No. The Chumash use it for purification.”

“The who?” I ask.

“Purify what?” asks Reek Pisserin.

“The Chumash are our local Native Americans,” Van Stein lectures. “They were here—in Santa Barbara—before anyone else. There’s a lot of ancient stuff going on in this area. They used sage to purify their souls, by smudging it on themselves.”

Van Stein lights a match and begins burning his dry vegetation, which he waves around, then purifies each of us, one by one, starting right ankle, up the leg, thigh, torso and shoulder, over the head, then down the other side, sage smoke filling the air around us. After snuffing out the flame, he smudges our foreheads with ash.

We depart Lucky‘s before they insist on it and shift our party westward to downtown Santa Barbara, the Palace Grill, for a recommencement of our communal brain-oiling, this time with a quart of Cajun martinis “for the table.”

The wait staff hand out lyrics and the restaurant goes silent to the first strains of Louis Armstrong’s What a Wonderful World. Everyone—servers, bartenders and the bums outside—join Louis and sing their hearts out.

And doesn’t end there. The last thing I remember is singing “Take me out to the ball game…” to the accompaniment of an accordionist. (And I probably kissed a contingency lawyer at some point because next morning I woke up with a blister on my lip.)