March 2003

Remember the days when despondent people ended their lives by jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge?

Now, according to the American Association of Suicidology, folks are cashing their final chips in Las Vegas, Nevada—the new suicide capital of the United States.

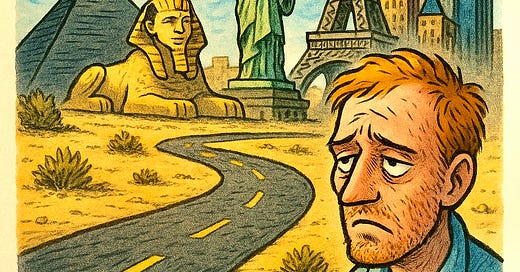

With Van Gogh haunting me, and on the basis that suicide is mostly a result of psych-ache associated with bi-polar syndrome, depression, and schizophrenia—and since the pursuit of insanity is our passion—the artist and I trek to Vegas with this mission: Find out why people are choosing a desert oasis known as Sin City as a exit of choice.

As first time visitors to Vegas, we would view with fresh eyes how America’s entertainment capital attracts and/or instills suicidal behavior.

I don’t gamble and I’m wholly indifferent to casinos, so this is not about rationalizing a gambling addiction, nor a way to visit Vegas as a tax write-off. (No auditor would possess the imagination to comprehend research like this.)

When your plane lands at McCarran International Airport (now named after Harry Reid), you think you can reach out and touch a view of the Southern Strip: a black pyramid, a sphinx, a Manhattan skyline—throw in a faux Eiffel Tower to evoke a sense of misplacement.

“It just looks like it’s near,” says our cab driver, flipping his meter. “An optical illusion. That’s what Vegas is mostly about. I should know, been here 40 years, the concrete business, helped build the place. It’s all a mirage.” (This was his gambit for taking the long way and raking in a high fare.)

He drops me at Mandalay Bay Resort, named for its concrete compound of swimming pools and beach mirage with simulated waves. Judging by the hordes that queue for an hour each morning to claim a lounge, you’d think this is Waikiki Beach. It’s a cool zone. For kids. If they were allowed in. Word is, Vegas is doing away with anyone shorter than 48 inches (except gambling midgets) after a decade of striving—with animal exhibits and medieval jousting—to reel in the whole family.

My room on the 28th floor features floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the Strip. But the windows don’t open, ensuring you cannot free-fall into the view but must continue breathing air vented from somewhere bowel-ish. There is nothing about this room begging you to feel at home. This is no accident; the interior decorators designed it that way. The owners want you out of your room, downstairs, gaming your money to them.

The Mandalay’s hub is a sprawling casino whose slot machines and card tables are positioned so that you cannot avoid them, whatever your pleasure, whichever your direction. Trekking a quarter-mile through the casino from Point A (the elevator) to Point B (a bar), I become disoriented and find myself back at Point A.

Can misplacement, optical illusion, simulation, and disorientation—individually or in any combination—lead to suicidal thoughts?

I need a cocktail, quick, to sort this through.

At the outer-reaches of Mandalay, the décor of Rumjungle includes a wall of tortoise shells. Alas, they are not relics of an endangered species, but another simulated mirage.

The artist is waiting at the bar. He’d flown in the day before.

“Sorry I’m late,” I say, “I got lost.”

“Happened to me twice yesterday. What I’ve discovered so far is everyone here is lost.”

Early Vegas operators baited visitors by offering cheap food and accommodation to pack them into casinos. Now almost every high-class restaurant in the United States has staked a presence in the USA’s Number One tourist trap—with high-class prices to match. Plus an attitude that says, There are more people than restaurant seats in this town, bub, so book early, like, a month ago, or duke the maitre d’.

You’ve already tipped the valet, the bellhop, and the concierge—the latter to squeeze you into a magic show at brokered price (a euphemism for three-times box office).

The artist is too broke to tip anyone, and that’s why he sits with an empty beer bottle at the bar, where the bartender ignores him. I order a beer for him, a martini for me.

“So what are we doing here?” he asks.

“Suicide.” I chew an olive at the end of my toothpick.

He looks alarmed. “Both of us?”

I nod. “It’s the 11th leading cause of death in the United States. What we need to find out is, why this place?”

“Drink up, I’ll show you why.” He had reconnoitered the town in my absence. “If you thought Iceland was mad…” he shakes his head. “I’m already on the verge myself. I think you have to gamble to keep your sanity.”

We walk a quarter mile through slots and gaming tables amid hundreds of people gambling their lives away, to the Mandalay’s taxi stand, wait our turn in line. “Where are we going?” I ask.

“Venice, Paris, New York.” The artist rolls his eyes. “You’ll see.”

Nine of the ten largest hotels in the world are in Las Vegas. Four of them share an intersection; 12,953 rooms on one corner—on most days, fully occupied.

We whip around themed resorts. First, Caesar’s Palace (ancient Rome). In Roman society, suicide was utilized to preserve honor and prevent confiscation of your family’s property if you’d seriously misbehaved. The slashing of wrists in a warm bath was invented here.

Luxor. Downing was the preferred method in ancient Egypt—so fountains do not spurt in this pyramid-shaped resort.

The Venetian (gondoliers on faux canals). Venice is where you romance the person who eventually breaks your heart, drives you to despair and suicide.

After that, Paris (fresh baguettes), a scaled-down Eiffel Tower, from which French suicides jump.

Finally, The Lost Village of Aladdin, where we got lost until discovering the only way out is—surprise, surprise—through their casino. This place is a composite of all countries Arabic, as if cultures in the Middle East are homogenous. Need I say… suicide bombers?

All ceilings (except Luxor) are the same blue sky with cloud—painted by the same bored Zoloft addict. Every so often, the ceiling flashes and thunder roars to simulate an approaching rainstorm. Looking up at blue sky with clouds, the artist shakes his head. “See what I’m talking about?”

I do. Las Vegas is a dead-end street with a low guard rail facing the abyss.

Odd thing is, those committing suicide of Vegas are not sticking to theme. They shoot themselves in the head or jump from multi-story car parks. No grand statement. No aesthetic exit ramp. No one has even thought to jump into the Volcano that erupts every hour outside the Mirage Hotel.

Within the obligatory shopping mall of each resort hotel is a clothing boutique called Bernini and another called Bardelli (same merchandise in both). You think, are these a pair of chi-chi Milanese designers who are on the cusp of discovery by GQ magazine? Closer inspection reveals the B Brothers are just another simulation-slash-con. What you’re really looking at is low fashion for the masses. (You can just see a middle-aged doofus back home in Toledo showing off his machine-made, unlined loafers: Got ‘em in Vegas. These babies are real Berninis!)

The kitsch up and down this five-mile strip is as unrelenting as the hot desert sun. Given time, both tempt you to either OD on something or pray to Pelagia, patron saint of suicides.

The American Encyclopaedia: “Suicide levels are highest among the unemployed, divorced, the childless, urbanites, and those living alone.” Also: More men than women commit suicide, a ratio of four-to-one; 73 percent of suicides are white males, and 55 percent shoot themselves.

Hence, if you live alone in a city, you’re divorced without children, you recently lost your job and you are a white male… steer clear of Vegas.

And more optical/audio illusions: Interactive movies that fool your mind and senses into believing you’re moving forward or backward, but never really going anywhere—except moments later through another casino.

“I’ve seen enough,” I say.

“There’s more,” says the artist. “A lovely hotel called The Palms.”

We taxi there. I enter The Palms and look around at yet another vast casino. “What’s lovely about this?” I ask. “It doesn’t even have a theme.”

“Exactly.”

The trendiest watering hole in Vegas, Ghost Bar, is on the top floor. But entry is reserved only to those who can prove they’ve spent at least 15 grand on rhinoplasty, face-lifts, tummy-tucks, breast implants, or liposuction.

“You hungry?” I say.

Onto the Hard Rock Hotel, a snooty reflection of its owner, Hard Rock Cafe co-founder Peter Morton, who forsook his burger-mongering roots to mint money as a casino operator.

We cocoon in red vinyl at Mr. Lucky and order from their 24-hour menu. Even the artist, who survives on Surf Dogs and Fat Burgers, can’t stomach this grub. The Buffalo wings and onion rings are indistinguishable from each other; lethal, ingested (or tossed—the likely outcome of ingestion).

Their club sandwich would likely be refused by a convention of starving hobos.

“Your trendy customers must smoke a lot of dope,” the artist says to our Bulgarian waitress.

“I not understand.”

“Only someone with serious munchies could eat this free-radical crap. What do you serve for dessert, Mylanta pudding?”

“We no have.”

“Too bad.”

She departs.

“If food and service was this bad everywhere,” I say, “reason enough to end it all.”

“It could have been worse,” says the artist.

“I don’t see how.”

“It could have been an all-you-can-eat buffet, and we could have been stoned. In the middle of the night we would beg Thanatos to rescue us.”

“Who?”

“The Greek god of death.”

We venture back to the strip, where pirates are exchanging canon fire with the Royal Navy outside Treasure Island. It draws a number of tourists clad in their new Bernini or Bardelli togs.

Watching such entertainment (tourists, not the battle), my epiphany is that Vegas is The Great American Temple, where believing is consuming, and the obese pray for yet a bigger all-you-can-eat buffet. After two days, you’re either hypnotized by the slots or nothing means anything. In other words, the hotels are full but the culture is vacant and people are numb. Someone needs to be sacrificed to Thanatos.

It is the casino carpets that ultimately tip the scale in favor of finito bon soir. They are all similarly garish. Could this be to conceal cocktail spillage? Guess again. These disturbing, obnoxious carpets are specially designed by psychologists to repel your eyes so that you cannot look down while you walk without feeling dizzy and disoriented. (Studies show that disorientation leads to suggestibility.) Instead, you are compelled to look ahead at the slots and gaming tables, which are adorned with flashing lights to grab your attention and haul you in. If you try to beat the system by making yourself look down while you walk, it drives you over the edge.

And there is a gift for paranoid schizophrenics who believe they are watching. Finally, someone is really watching. You don’t see policemen along the strip. But that’s because the strip does not need policemen. Their sophisticated eye in the sky can track you to Paris and back—and record for posterity photos of you picking your nose (although they probably miss Muhammed and Mukhtar from Aladdin casing New York, New York). The artist is already looking over his shoulder, hissing at invisible surveillants.

So… you are already feeling low and the carpets (and everything else) have fried your brain, along with trillions of free radicals in your bloodstream from too much fried food. There’s a better edge for checking out than Las Vegas—and it’s still considered part of the Vegas experience.

You know how your whole life is supposed to flash before your eyes when you jump off a building? If you leap into the Grand Canyon, there’s time—a full 15 seconds—for all your past lives to flash before you too!

You can roll into Vegas, take a final look at Paris, Venice, and New York; do memory lane—ancient Egypt and Rome—for your ancestors’ sake. Wallow in simulation. Then spring two C bills for an Air Vegas flight over Hoover Dam and Lake Mead, to a tiny airstrip on the Grand Canyon’s west rim.

The artist and I opt for platinum service, a couple hundred extra. You get picked up by a stretch limo, they take your photograph standing next to a cactus outside North Las Vegas Air Terminal, and you get a private tour instead of joining the cattle train.

Then, board a plane (no ID necessary, no security for checking backpacks, as if 9/11 never happened, even though juicy targets abound…).

Wendy the guide welcomes you and she wants you to board the return flight to Vegas. But even if you tell her your plan, there isn’t much she can actually do about it. For not only is there no landline telephone service on the west rim, there is no cellular service either.

Danger lurks everywhere, says Wendy. There are rattlesnakes, scorpions, large hairy spiders—not to mention rotor blades of the helicopter that lowers you a mile down to the canyon floor. A brutal wind shear claims a handful of sightseers every so often.

“One of these babies crashed five weeks ago,” the artist whispers. “They lose them all the time.”

A whole book has been written about people who perish at the Grand Canyon—most by accident, not design.

At the bottom, a flat boat cruises you along the Colorado River for 20 minutes. Then a return flight to the rim, where Wendy carts you to a Native Indian outpost staffed by Hualapai Nation, who lay on a last supper: An all-you-can-eat buffet of BBQ beef, baked beans, corn-on-the-cob and a warm tortilla. Not only do calories no long matter, you probably want bulk for a final descent.

The artist and I stand at the edge, surveying the awesome panorama—and the drop.

“Ready?” I say.

“Forget suicide,” says the artist, “this is murder.”

“Murder?”

“Those Indians are trying to murder palefaces with that meal.”

“You’re worried about cholesterol?”

“No, flatus. One tail-shot and it’s over the edge. Geronimo’s Revenge.”

I step back.

But if I were inclined to check-out, it would be here, at the Grand Canyon, not a multi-story parking lot in Vegas. After all, this is your life you’re concluding. Why make your last stop in a tacky town built specifically to con everyone out of their money, their mind, their life; why end it there when, without much further effort or expense, you can fossilize with a two billion year-old wonder of the world?

Alas, I’m still here.

Everyone considering suicide should stick around, too.

We’ll all have plenty of time later to be dead.