THE BILDERBERG GROUP

A Santa Barbra News-Press Column from August 2021

The annual Bilderberg Meeting is taking place this weekend in Madrid, Spain.

High on its list of key topics is State of AI and AI Safety.

Alas, for the first time in seven decades, Henry Kissinger will not be present.

I first became a journalist (in 1976) by investigating a topic most folks considered to be little more than a right-wing conspiracy theory.

I’m talking about the Bilderberg Group—an assembly of movers and shakers, captains and kings from North America and Europe who meet annually in secret for lofty discussions on how best to mesh their beliefs about how foreign and economic policy should be shaped going forward.

My research began while I was a student at American University in Washington DC where, from my dorm room, I wrote to numerous government agencies and foreign embassies seeking more information. No one was forthcoming; in fact, even those who acknowledged Bilderberg’s existence knew (or would say) nothing more.

This reply from the (UK) Foreign and Commonwealth Office: “Unfortunately, we can find no trace of the Bilderberg Group in any of our reference works on international organisations.”

(Never mind that Denis Healey, Britain’s chancellor (treasury secretary) at the time, was one of Bilderberg’s founding members.)

A State Department flunky named Francis J. Seidner, a “Public Affairs Adviser,” even advised me to mind my own business.

Some people thought I was nuts. They said I was a “conspiracy theorist.” And they tried to discredit any talk of Bilderberg by associating it with folks who write about the Illuminati, an actual secret society created in Bavaria in 1775 by Adam Weishaupt, who believed that the Freemasons (another secret society, to which he had formerly belonged) were not doing enough to bring about revolution.

Yet Bilderberg had been meeting secretly since the mid-1950s with the specific objective, to the best of the abilities of participants within their various spheres of considerable influence, of manipulating the foreign policies and economic platforms of Western European countries and the United States.

After three months of walking a labyrinth, I tracked down a charity in New York City called American Friends of Bilderberg. I visited the low-profile if elegantly-appointed office of the mundane-sounding Murden & Company (a cover) in midtown Manhattan and received a cordial reception. This was where Bilderberg’s Steering Committee, in coordination with a European Steering Committee, based in The Hague, decided agendas and participant invitation lists for upcoming Bilderberg meetings.

I earned an A on the term paper I wrote about this for my International Politics course. More important than a good grade, the thrill of the search incentivized me to pursue a career in journalism and, indeed, an obscure British magazine soon reshaped my term paper into a lengthy feature story.

But even those who read it questioned whether the existence of such a group was for real or fantasy, such was the power of those who would cast “conspiracy theory” aspersions on any mention of Bilderberg.

Until April 1977.

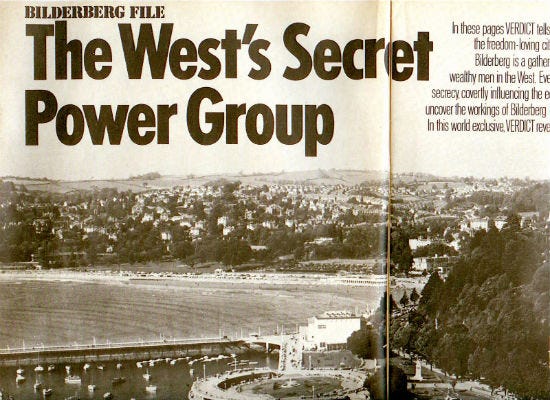

That is when the Bilderberg Group next met, in Torquay, on the Devonshire coast in southern England. (Bilderberg traditionally stages its three-day conferences at alternate five-star resort hotels in Europe and the USA. The meeting they were supposed to have convened in Williamsburg, Virginia in spring 1976 was cancelled after Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands was caught taking bribes from the Lockheed Corporation and forced to resign in disgrace as Bilderberg’s chairman.)

I had forecast the Torquay conference in my magazine piece, identifying the luxury Imperial Hotel as its venue.

This marked the end of Bilderberg’s anonymity.

Because, sitting in the Imperial’s lobby, a smattering of Fleet Street reporters, all in possession of the actual magazine in which my story had appeared six months earlier, appeared to be taking bets amongst themselves on whether or not any such so-called “Bilderbergers” would actually manifest themselves.

And suddenly, like gnomes, there they were, as the lobby began to fill with the likes of Henry Kissinger, NATO Secretary-General Joseph Luns, Fiat’s Giovanni Agnelli—and even German Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt—leaving seasoned reporters with mouths agape.

I was there myself watching when a white Range Rover deposited a rumpled David Rockefeller at the Imperial’s front entrance.

Mr. Rockefeller, then chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank and unofficial chairman of The Establishment, was shocked to see reporters and photographers milling around, flashbulbs popping. And they were just as shocked to see him. (I should probably have introduced myself to him as the reporter responsible for this debacle.)

Bilderberg was for real. And no longer secret or anonymous.

I, a rookie of 22, was the only reporter among several veteran newspaper luminaries who knew anything about the secretive group.

I got wined, dined, grilled and willfully exploited—and for the first time in its 23-year history, the existence of Bilderberg got reported by the mainstream media—to include the (UK) Sunday Mirror, (London) Evening Standard and Bill Blakemore of ABC News, with whom I’d consulted a week before the confab. (I wrote my own story for a New York-based weekly magazine called Seven Days, which commissioned me to report from Torquay.)

This is what I was able to tell them:

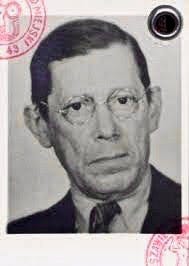

Bilderberg was rooted in a 1946 address by Joseph Retinger (a Polish political philosopher) to the Royal Institute of International Affairs in London. His topic: The threat posed to Europe by the Soviet Union. This speech spawned the idea of a European Movement.

Utilizing his high-level contacts as an eminence gris, Mr. Retinger harnessed Prince Bernhard to figurehead his project. Realizing the need for American support, he and the prince together traveled to the USA to recruit super-banker David Rockefeller and CIA Director Walter Bedell Smith into the mix. (The CIA, through a cover entity called the American Committee for a Unified Europe, had, earlier, secretly channeled more than $3 million to Mr. Retinger for moving his movement forward.)

In May 1954, in Oosterbeek, the Netherlands, at Hotel de Bilderberg (from which the group took its name), 80 of the most influential men from Western Europe and the United States spent three days bonding and super-networking.

They arrived at this conclusion, stated in the confidential minutes of that event:

“When the time is ripe, our present concepts of world affairs should be extended to the whole world.”

Their main concept in that era: A unified Europe.

And, acting from behind the scenes, in secret, they succeeded.

The late George McGhee, former U.S Ambassador to Germany once declared, “The Treaty of Rome, which brought the Common Market into being, was nurtured at Bilderberg meetings.”

Ambassador McGhee would know. He attended a Bilderberg meeting—in Garmisch, Germany, September 1955—when, according to the confidential record of that meeting, “It was generally recognized that it is our common responsibility to arrive in the shortest possible time at the highest degree of integration, beginning with a common European market.”

The European Movement turned into the Common Market; the EEC turned into European Union; and, simultaneously, an Atlantic Alliance flourished.

But while they managed to stave off another WW in Europe—their main objective—they made a cockup of the rest of the world, from the Vietnam War to Middle East policies, from selling out Western manufacturing to China to not keeping its promises to republics once part of the USSR—all the way to Afghanistan.

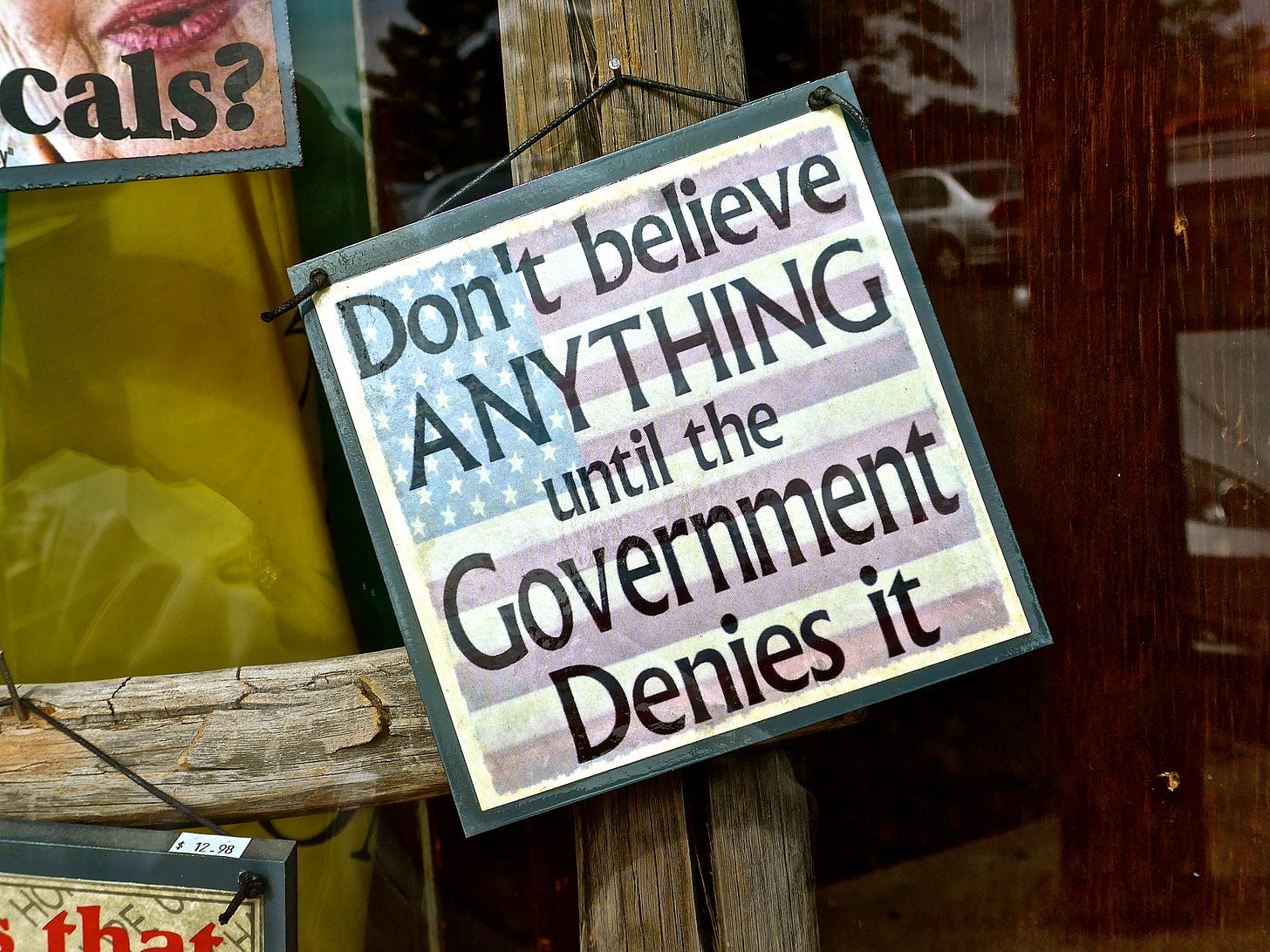

If there is a moral to this story, it is this: When any powers-that-be use the term “conspiracy theory” to cast aspersions on a subject for the purpose of discrediting whomever is trying to learn more about it, it signals time to triple-up efforts to investigate and intensify the spotlight on those who prefer to keep us in the dark.

For instance, the notion that COVID-19 was developed in the Wuhan Lab, partly funded by the National Institute of Health with Anthony Fauci’s blessing, is not conspiracy theory. It is actually a no-brainer (though too bad we’re surrounded by people with no brains). In time, when all the dust has finally settled and polemics are removed from the process, post-mortems will most likely concur this as fact.

Until recently, anyone and everyone who expressed a belief in UFOs over the last 70 years was, according to the U.S. Government, a certified conspiracy theorist; yet now we’re told by the Director of National Intelligence that UFOs “clearly pose a safety of flight issue and may pose a challenge to U.S. national security.”

What a turnaround!

Concerns that the experimental COVID-19 vaccine may be unsafe for some folks in the long-term are legitimate issues (conceded by the Federal Drug Administration) and not merely the domain of “anti-vax conspiracy theorists,” as anti-social media might have you believe, censoring the likes of U.S. Senator Rand Paul for not buying into their preferred narrative, along with quashing any news about therapeutics being used to successfully beat back the novel virus.

The term “conspiracy theory” has become vastly over-used and abused, casting a pall over a constitutional right we hold sacred: freedom of speech and expression.

“It was the CIA who in 1967 first injected the term conspiracy theory in the public lexicon,” wrote Peter Janney in his remarkable book, Mary’s Mosaic. “A term that has continued today to be used to smear, denounce, ridicule, and defame anyone who dares challenge a prevailing mainstream narrative about any controversial high-profile crime or event.”

Rule of thumb: Never believe whatever the government tells you; they lie about everything.

Or, as this sign in a shop window states…

What. you have written and unearthed as a Journalist/ intrepid Reporter is truly amazing Robert,

your #1 fan in TL/WA