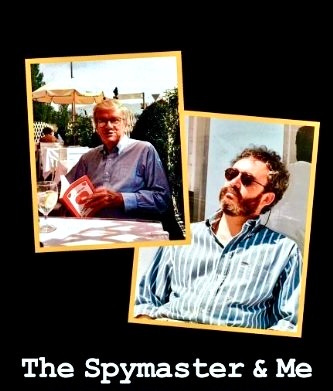

Clair George and I jetted to Geneva on other business (our countess). While strolling the promenade along Lake Lemann, two ideas struck me: The first dealt with the old League of Nations building, which, derelict for many years, was finally being renovated to become Centre d’Environment. As such, it might provide an ideal setting for our water project. (Herbert Bloomfield had already determined that he wanted a European address for our venture “to internationalize it.”) The second idea dealt with a name for our water business. Inspiration struck when I contemplated Geneva’s Jetto, the landmark fountain that shoots water three hundred yards straight up into the air.

Jeatteau International.

Toasting our prospective company name and address inside Tse Yang, the Nova Hilton’s Chinese restaurant (enjoying a view of the Jetto), Clair and I gobbled steamed dumplings while composing a jocular letter to Herbert about “pollution busters” and “saving the caviar,” each adding a phrase to complete the other’s thought, enjoying the high L.Q. (laugh quotient) of this project.

It was during this Euro trip that we inadvertently ran into Prince Albert of Monaco then met with him at the Palace (written about earlier in this saga). We told the prince about our water project with Herbert and asked if he would like to play a role. “Of course,” replied Albert.

At our next meeting in New York, Herbert introduced a new character named Andre into the mix. Herbert was vague about what Andre’s role would be; later, I discovered that Andre himself was puzzled about what Herbert expected him to contribute.

By now, Clair and I sensed that Herbert operated not by instinct but on impulse. The simple reality was that Herbert had no real plan; this venture would evolve whimsically—the ready, fire, aim approach.

Rather than question or object to this management style, we simply deferred to whatever bout of whimsy Herbert displayed during five meetings through the summer.(Clair was a great believer in putting in an appearance, even if it had to be contrived, because it meant face-time and continuity. Without that, he reasoned, a busy, important client might easily forget about you.)

In early autumn, six months after we’d begun, it was becoming clear that Herbert might never, as promised, identify a business manager to spearhead our water enterprise.

Joy had moved to Israel on Herbert’s dime to study water projects in the Middle East. Then Andre turned up in Tel Aviv and Joy got spooked by his incessant e-mails to her.

With this insanity going on around us, I decided to choose my own business manager, and posited this to Herbert.

“Sure,” he shrugged. “I’ve been waiting for you to suggest that. Bring him to see me.”

Enter Alan, marketing background, good with numbers, very sharp. Not a water expert, but no matter. I recruited him over a latte at Starbucks.

Two weeks later, Clair and I introduced Alan to Herbertville, and Herbert put Alan on retainer.

We needed an office to anchor Alan. Herbert instructed us to find one.

Alan and I toured office accommodations in the Washington area and settled on a three-room suite above Sutton Place Gourmet on New Mexico Avenue.

Alan wrote an invoice to cover everything and we Fedexed it to Herbert-ville. The funds—over $100,000—arrived by wire next day.

Alan went to work and we soon learned that water, as a subject, is as dry as the Aral Sea.

A whole industry already functioned to save diseased rivers and lakes throughout the world. Know-how and technology was available. However, most countries were unwilling to swallow the building and operating costs of such technology, preferring instead to pour their state budgets into weapons and ammunition. Heads of government did not wish to pay to clean their water, preferring that the World Bank pay to study the problem and then pay even more to fix it with humanitarian aid coming from elsewhere.