Clair and I shuttled to Herbertville to assess the end of our water biz partnership.

“I need to look into Herbert’s eyes,” said Clair, who could figure out, through a good eye gaze, what someone was truly thinking.

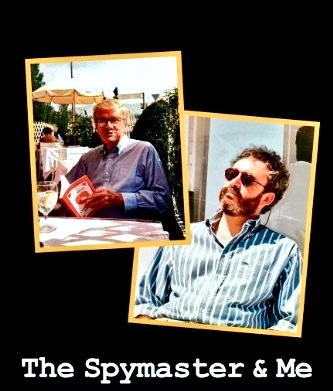

“Ah, it’s the one-two punch,” Herbert greeted the spymaster and me. “Just the guys I want to see.”

Clair and I exchanged puzzled glances; a whim-whim situation.

Herbert sat us down and explained that he had ventured into a partnership with a Ukrainian named Vadim, and that The New York Times had just exposed Vadim’s links to organized crime. Herbert wanted to know, just how bad is he?

Clair and I were put on retainer to investigate.

Water was never mentioned once.

“What was he thinking?” I asked Clair over hamburgers at Soup Burg, corner of Madison and 69th, assuming Clair had penetrated his brain.

Clair shook his head and cupped a hand conspiratorially around his mouth. “It’s very simple,” he whispered. “Herbert is insane.”

Clair chose the right source to get the goods on Vadim, who was worse than anyone could ever have imagined. Many years earlier, he had sold his soul to the KGB; his finger pointing had led to the arrest, imprisonment and execution of others.

We delivered our Vadim file to Herbert. Though mortified, he was at a loss over what to do about it. They were, after all, already partners.

“President Kuchma personally recommended Vadim,” said Herbert. “I’m supposed to go to the president and say the guy you recommended is a spy and a crook? Anyway, Vadim isn’t my partner anymore.” He pointed at Dick, the water biz killer. “He’s his partner.”

The courtiers of Herbertville tittered.

They had another investigation for us: a Pole that opposed a project Herbert wanted to tackle in Poland.

We dug up dirt.

Next, due diligence on an individual Herbert was considering for a top position. We gave him a clean bill of health and he got the job.

Next, an investigation of an American businessman in Kiev who had filed a lawsuit in New York against Herbert in which he alleged unfair competition, improper payoffs and corrupt methods. Our investigation showed that it was the businessman who had taken illegal cash bribes and then laundered his booty.

So impressed was Herbert by our capability to acquire sensitive information, he had a new investigation in mind when next we met: Herbert wanted us to dig into the prime minister of a Central European country.

Truth was, the prime minister had been recruited by the KGB when he was 18 years old while attending university at Rostov-on-Don and had secretly collaborated with the KGB for 50 years. He helped the KGB quash a rebellion in his country and the KGB nurtured his political career.

Herbert was pleasantly amazed by our findings. “We could bring him down with this,” he grinned. “How would you do this?” he asked Clair.

“Well,” said Clair, “it’s one thing obtaining highly sensitive information for ourselves and quite another going public with it. It will be obvious where the information is coming from and would therefore put our operatives at risk.”

“Okay, okay.” Herbert paced around the conference table. “I’m prepared to spend several hundred thousand dollars on an operation that would topple him. Come back to me with a plan.”

We returned to Herbertville three weeks later: With the consent of our sources (who would be paid handsomely for their risk), Clair would take the story to a major U.S. newspaper, whose key editor he knew socially. To make it seem like the prime minister was not being personally targeted, Clair would throw in Vadim and the Pole. If the newspaper ran this story and exposed the prime minister as a long term Russian agent, it would scuttle his chance for reelection six months down the road.

Herbert loved the plan—and refined it with a twist of his own: Add two additional persons to the mix for further muddying.

Clair’s source came up with two new dossiers.

The first, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, confirmed that the KGB had recruited this ultra-nationalist politician to create his political party and dilute election voting.

The second was a nephew of Boris Berezovsky, the Russian oligarch.

Herbert was thrilled. “Can we keep it secret?” he asked.

Replied Clair, “As I said to President Reagan when he asked if we would be able to keep our arms for hostages operation secret: Of course.”

Clair went to see the newspaper and laid out the story in general terms, without identifying the prime minister or any of the others.

The newspapermen salivated.

All we needed was the project fee, a half million dollars, which included paying sources for their risk.

Herbert balked, busy with other matters.

Three months passed.

Come mid-May, the Central European country held its election. Although the incumbent prime minister was favored to win, he lost. Consequently, action was no longer needed.

Herbert finally got bored with his new toy (the spymaster and me) and turned elsewhere to satisfy his bouts of whimsy.