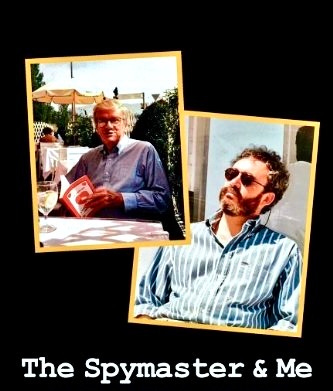

THE SPYMASTER & ME: 36) "ALWAYS KEEP THEM GUESSING"

A Throwback Thursday Memoir of Intrigue & Lunacy

And that’s how it became my job, through Clair George and on behalf of FBI counterintelligence, to create a sting that would attempt to snare America’s most wanted spy.

Soon, however, the FBI fumbled. They simply could not get it together due to their rigid rules.

But then I experienced an epiphany: I was not bound by FBI rules. My generous offer had been engulfed by bureaucratic indecision and ineptitude—yet I had no obligation whatsoever to the FBI. (Despite some media referring to me as “a former FBI agent,” I have never been, nor claimed to have been, a special agent fully employed by the Bureau.)

My inspiration for playing it my own way was Alexander Bott, a 17th century man of letters, who wrote:

I am not a believer in the foolish system of literal obedience, but rather in that higher form of discipline wherein a subordinate obeys not the order which he has actually been given by a superior, but rather the order which that superior would have given had he known was he was talking about.

I would edit Howard’s book. If the FBI terminated its relationship with me, so be it. I had offered my services in good faith and done everything on my end to make it work. I would establish a working relationship with Ed Howard and, working alone, I would attempt the same goal: his capture.

I phoned FBI Special gent John Hudson in Albuquerque with my pitch: “If you get a final green light, fine. If you don’t, I understand. But I’m doing it anyway. Feel welcome to call me for updates.”

Hudson was not enthusiastic. “The problem,” he explained, “is those Big Cheeses have big egos. They may say no way about picking it up later.”

“Look,” I said, “I know you’ve got your rules, and you’ve got to stick to them. But I’m not bound by those rules. You and I both know in our hearts I’m doing the right thing. I got into this situation with a view towards helping you guys and I’m sticking to that. But I’ve got to do it my way because otherwise it’s going to slip away because your senior bureaucrats can’t get their act together.”

“Okay,” said Hudson. “Let me make some calls.”

While Hudson made his calls, I lunched with Clair at Melio’s, our occasional alternative to DeCarlo’s in Spring Valley, northwest DC.

I asked his advice on my new stance.

Clair listened, nodded. “Fuck ‘em,” he finally said. “If you want to edit the book, do it.”

“Yes,” I said. “But with a view to nailing Howard.”

“No problem,” said Clair. “I’ll tell CIA you’re going to edit this book, that the lawyers at Justice are messing it all up—hell, it probably went to Janet Reno, and she said, why can’t this guy just come home.” Clair shook his head in disgust. “We’ll meet with Dick Stolz this weekend and you’ll tell him what’s going on. He’ll go out to Langley and tell Tom Twetten and Ted Price that you’re going to do this and keep them informed.”

FBI Special Agent John Hudson phoned me from Albuquerque. “We’re in agreement for you to do it your way,” he said. “Meanwhile,” he added, “take good notes.”

“Don’t worry,” I said. “I write everything down.”

Then Clair phoned. “Dick Stoltz says you’d be crazy not to do this. He says, just go ahead and he’ll sort everything out with CIA.”

Then Clair lunched with Tom Twetten, deputy director for operations, and they discussed my Howard project, concluding I should keep moving full speed ahead, with or without the FBI.

I conveyed to Clair the latest in a series of Bureau “glitches.”

“To hell with the feebs,” he said. “Don’t listen to them if you don’t want to.”

Nonetheless, I continued to feed the FBI updates—and listened to Hudson hum. Literally. Hudson had taken to responding with hmm to everything I said, a kind of detached deniability if things went wrong.

Soon, Howard Fedexed a letter inviting to meet me in Zurich, Switzerland.

I faxed it to Hudson—and also to Clair, who faxed it to Twetten.

Hudson responded by saying his pace for getting things approved had slowed down.

I was astonished, not appreciating things could move even slower than before.

Then he called back a few days later, somewhat bewildered. Had I, he asked, shown Howard’s letter to anyone else?

“Uh, yeah,” I said. “Clair George.”

The Agency had sent Howard’s letter to the Bureau at the highest level; it had caused the FBI’s bureaucracy to snap, crackle and pop.

“Sorry,” I said. “I hope it didn’t embarrass you.”

I phoned Clair upon his return from a two-day mission in Rio de Janeiro and told him our tactics had backfired.

“Are you kidding?” said Clair. “That’s how you get things done in government! Now somebody is doing something!”

Of course, Clair was right.

Hudson phoned a few days later. “Looks like we’re getting somewhere,” he said. “I’ve been called to Washington for meetings.”

Finally, the FBI jumped into gear.

I worked on Howard’s book, and travelled to Moscow in July 1994 to see the traitor on his turf. A few months later, Howard and I met again in Switzerland. (A fuller, much more detailed account of this will commence in a few weeks.)

The FBI invited me to the J. Edgar Hoover Building. I was charmed, of course. That’s because I was not yet aware that most FBI field agents strove to avoid headquarters. I would presently discover why.

I’d been working the Howard case for 14 months by then. It somehow qualified me for an ambush. Faces I’d not seen before—five, to be precise—surrounded me in a windowless and rather soulless conference room.

Hudson cued me to tell my story: journalism, book packaging, creative problem resolution, private-sector intelligence. I laughed a lot; the assembled company did not.

After I finished, a man named Dick asked me questions about how I might feel if, after spending time with Ed Howard, he was caught and put behind bars.

I shrugged. “I’m used to pulling ruses like this. The whole point of this project is to capture him.”

In fact, it had been my idea.

Mildly patronizing, Dick said that people never really knew how they would feel until such a situation was upon them—so would I mind taking a battery of psychological tests?

Next it was Bob’s turn. “Why does Ed Howard trust you so much?” he asked suspiciously.

“Because I’m good at what I do,” I replied.

It went on and on.

Later that day, I met with Clair and related to him all that had been said.

He listened, bemused at first, and then incredulous that 14 months after I’d started working on Howard, the FBI had only just now concerned itself with operational security.

As for the psychological tests, said Clair, “Tell them they can shove their battery of tests up their...”

“I already did.”

We laughed, as always. The L.Q. (laugh quotient) had never been higher.

A new FBI glitch soon materialized: one that had nothing to do with how I would feel push come to shove nor with operational security, the latter of which we’d simply resolved by creating a special telephone number for communications between Special Agent Hudson and myself and purchasing a safe for my home.

I heard about it from Hudson over cappuccino at Au Bon Pain in the shadow of the austere J. Edgar Hoover Building before reentering headquarters (my second visit), where a couple of Big Cheeses would join us.

The new glitch in a nutshell: The Justice Department was waffling over evidence. They needed more. They wanted a log that they believed was hidden in Howard’s laptop computer—and they wanted me to steal his hidden files from it, in Moscow.

Clair gasped when I told him what the FBI wanted next. “This is starting to sound like a shitty novel,” he said. “What about your wife and children? Are the feebs planning to look after them if you get thrown into the slammer for 20 years? No, you’ll be on your own. Tell them this isn’t what you signed on for.”

Howard’s book got published. As his editor, I ensured that sensitive information related to the national security of the United States was deleted before publication. And I slid Howard into a new book of my own making, Spy’s Guide to Europe, which I conceived especially to draw Howard out of Russia, to various Central European capitals.

It was important to move National Press Books out of the equation as its principles had no knowledge of my true objective.

Eventually, we hit pay dirt. Howard planned a trip to Warsaw, Poland, to research Spy’s Guide—and FBI Legats in Warsaw obtained permission from the Polish government to intercept Howard at Warsaw Airport while he walked from the plane to Immigration through an international corridor.

However, at the eleventh hour, as FBI agents (in coordination with CIA) prepared to pounce, the Justice Department balked and aborted the operation. Apparently, that order came directly from the White House.

The United States could have captured the only CIA officer ever to successfully defect to Moscow—and chose not to go through with it.

The person least surprised was… Clair George.

So the FBI gave up trying to apprehend Edward Lee Howard, and instead I set to work, on their behalf, gathering positive intelligence from Howard and his buddies in the Russian intelligence services.

To that end, I returned to Moscow, twice, to ruse former KGB chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov, who wanted to write a book for Western consumption. I also traveled to Havana for a crack at Howard’s buddies in Cuban intelligence.

Departing Havana’s Jose Marti Airport, I bought Clair a Che Guevara Swatch Watch to wear at his next dinner party.

As my missions for the FBI evolved into rusing Cuban intelligence agents stationed in Washington, D.C. along with hastening the extradition from France of hippie-guru murderer Ira Einhorn, Clair watched with amusement, providing sage advice.

As always, his best advice was this: “Keep everyone laughing half the time, scared the other half—and always keep them guessing.”

My experience with the FBI reminded me of another Clairism, something he’d told me soon after we first met: “I’d take you downtown [Washington] and introduce you to the people who run things [in the U.S. government], but it would only scare the hell out of you.”