THE SPYMASTER & ME: 38) THE JEFFREY ARCHER BREAKFAST CLUB

A Throwback Thursday Memoir of Intrigue & Lunacy

April 2000

Spying is awfully like a drug. It is a great high while you’re doing it, traveling on a mission—or several missions entwined, which is how I operated, handling several clients at once, all sharing expenses.

But when you’re not, the comedown is a bitch.

One day, you’re mixing it up with Russians in a foreign capital, a total adrenalin focus, puffing on Cuban cigars, sipping vintage Armagnac, watching for watchers.

Next day, you’re home. The six year-old needs a bath, the teen, some counseling, and the dog, a walk.

That’s why I was glad to be back on a jet flying toward London and the French Riviera for a new round of intrigue.

My novels about espionage had become almost prophetic: Plots and characters transformed into reality.

As for my report writing, I enjoyed the most exclusive readership in the world: A limited circulation of government employees cleared to read my prose on a need-to-know basis. As I understood it, my reports were sought after for their entertainment value alone.

But nine years of espionage was not without some fallout.

A few months earlier, Clair and I had been named as defendants in a lawsuit against The Circus, to which I alluded much earlier in this memoir. Media interest in the case suggested that my ability to operate undercover would soon come to an end.

It was under such circumstances that the spymaster joined me on this trip to Europe. We had to see the countess—perhaps our final visit (together) with her—and I had to wrap up a couple of undercover assignments before my exposure as “a spy and saboteur” reached the public eye.

While in London, we attended Jeffrey Archer’s Breakfast Club.

Archer, the best-selling novelist, was deputy chairman of the Conservative Party in 1984 when I helped him organize his first breakfast for a visiting U.S. political leader.

Our guest on that occasion: Jack Kemp, then a U.S. Congressman from New York with higher political aspirations.

Jeffrey managed to assemble almost all of Margaret Thatcher’s cabinet to meet Rep. Kemp over scrambled eggs, kedgeree and orange juice, champagne and coffee, in his penthouse apartment (a museum of fine art) on the River Thames overlooking Westminster.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, this became Britain’s most exclusive breakfast club.

The downside: It was cursed.

Kemp was unsuccessful and divisive as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under the first George Bush; he did not attain his presidential or vice-presidential ambitions—and died of cancer at age 73.

Lord Archer’s next guest was New Jersey Governor Thomas Kean. Also perceived as a high-flyer, Kean went nowhere after his governorship ended.

Third guest: The former U.S. Senator from Texas, John Tower. Thereafter, his former U.S. Senate colleagues would reject Tower as George H. W. Bush’s choice for Defense Secretary. Two years later, Tower died tragically in an airplane crash.

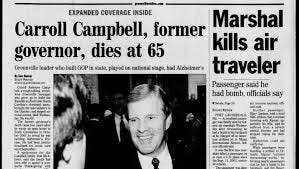

Fourth guest: Carroll Cooper, Governor of South Carolina, gearing up a run for the White House. But when diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at the age of 61, Cooper was forced to abandon his campaign for gubernatorial reelection—and died from a heart attack four years later.

Jeffrey Archer himself: Sentenced to four years imprisonment for perjury and perverting the course of justice.

On this trip, Clair and I attended Archer’s breakfast for… Newt Gingrich.

Newt introduced his then-wife, Marianne, as “the love of my life” (a love cursed, thereafter).

Clair was delighted and amazed to meet the Tory party’s opposition ministers (if less enamored by Newt)—and much amused by how they introduced themselves. “Hello, I’m Shadow Defense.”

When we returned home, I wrote up the experience as a mock news story.

On his first trip to London, House Speaker Newt Gingrich blamed the deficit on diabetics. “They go blind and have to have their feet amputated,” he said. “It costs 23 percent of all Medicare. Once we stop these diabetics, we’ll have no further need for inheritance tax—and our social security ills will be resolved.”

Addressing shadows at a shadow power breakfast given by Lord Archer, Mr. Gingrich said the only way to keep U.S. troops in Bosnia was to bamboozle the American public. This was not difficult to do, he added, since the average American never thinks about Bosnia—or anything except “paying their bills, getting their kids to soccer practice and deciding what movie to see over the weekend.” Said Gingrich: “If we rotate our troops from Hungary to Bosnia, no one will notice.”

Mr. Gingrich declared the importance of emphasizing value over efficiency, pointing out that the cell phone was invented in Chicago, not Tokyo—and he hailed the fax machine as the greatest invention of our time.

Clair howled with laughter.

In return for Jeffrey’s breakfast, Clair took me for lunch at DeCarlo’s with legendary CIA director Richard Helms.

The reason Clair, himself, became legendary among CIA colleagues was partly because he went to Athens when no one else at the agency wanted the job and, instead, ran for cover. Richard Welch had just been assassinated by a Greek terrorist organization and they needed a new station chief to fill the position. Only Clair was willing.

The agency tried to sweeten the deal. For a start, they’d buy a new residence for the new station chief.

Nothing doing, said Clair, I’ll live where Welch lived.

Okay, then we’ll put up ten-foot high gates.

Clair said, Nope. He refused to hide himself. Instead, he enjoyed nightly cocktails on the residence’s front porch, in public view. Clair understood odds as well as any actuary and, like an actuary, he knew the odds favored him.

When Clair served in Beirut, and civil war raged around him, he’d take his dog for a walk on the promenade—to the horror of his British counterpart.

There’s a downside to this story, to do with fate, that Clair lived with, and revealed to me:

Soon after he became deputy director for operations, a young female officer who had never been overseas pulled him aside after a meeting. She was about to embark on a brief visit to Beirut, her first trip abroad, and she was anxious about it.

“Will I be okay, Mister George?” she asked.

“Relax,” Clair assured her, his standard response. He knew the odds were way on her side.

Tragically, she was among a number of CIA personnel killed when a suicide bomber detonated a bomb after crashing into Beirut’s U.S. Embassy.